For more than 60 years, Jacquetta Nisbet ’46 has been learning, practicing and teaching the ancient textile traditions of Native American and First Nation cultures. One of North America’s premier weaving artists, she has created works represented in collections around the world, from a 15-foot double-woven light form for Pasadena’s California Design X show, to a ten-footwide wall hanging for Nordstrom.

Born in Malaysia and raised in Edinburgh, she emigrated to the United States and now lives in British Columbia. Jacquetta embodies cultural exchange. Her interest in weaving began on an unlikely corner of New York City’s Madison Avenue. She and husband Nory spotted a classic, woven weft-brocade belt from Guatemala in a store window. Jacquetta took one look and thought, “That’s me!” She bought it and began her studies.

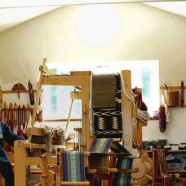

Jacquetta immersed herself in the weaving practices of Navajo, Hopi, Central and South American, Persian and Asian traditions. A “class” on Peruvian pebble weaving does not exist, however. It’s a tradition more than 4,000 years old, and the only way to learn it, Jacquetta explains, is to “start reading, and then get busy.”

These traditional techniques are methodical, detailed and exacting—best learned through work on the loom while studying with indigenous masters. Jacquetta spent time in New Mexico under the tutelage of Navajo weaver Sarah Natani, whose advice to the gringa was simple, but diffi cult: Don’t worry about the end result. Have fun—it’s an adventure! Shed the goal-oriented standards of Western culture, and don’t be concerned with mistakes.

Jacquetta has demonstrated this elementary toe loom while waiting at the doctor’s offi ce or at the airport. “I usually gather a few curious bystanders who wonder what the hell I’m doing! It’s another way of teaching.”

“This idea—less competition, more cooperation—makes life far more interesting, and it takes the heat off,” says Jacquetta. “In Navajo tapestry weaving, you work with no drawn plan, no cartoon. You go from the terra fi rma you’re standing on into the chaotic unknown. The most extraordinary things happen while working this way. The integration of your conscious and subconscious intellect, your heart, mind and hands—the whole gig— is very exciting.”

Tribal traditions value balance, humility and ritual, values that Jacquetta shares but fears have been eroded in the electronic buzz of modern life. In ancient weaving traditions, this hands-on, spiritual artwork becomes significant on a universal level. Each object is created as an offering. In Peru, for instance, before beginning a piece of weaving, you offer coca leaves and chicha, corn beer, to Pachamama, Mother Earth. The Incans regarded textiles to be the most important commodity after food production. They still do. In Guatemala, symbols woven into the colorful, weft-brocade huipiles were a vital means of sustaining the universe through their images.

One of the challenges Jacquetta welcomes is sitting down with people of another culture and learning their way. “I purposefully go outside my comfort zone. In these situations I feel out of place, and I’m aware of my cultural corners. I say very little. I just listen. I experienced this with a Coast Salish wood carving group, and while taking sumi-e brush painting lessons from a Japanese master. I don’t know of a more powerful teaching moment than simply listening, being very quiet in your own spirit and drinking in what others have to share with you. Don’t worry about your own discomfort. Shelve your opinions for the moment. Be as noncritical, sensitive, and respectful as you can. My goodness, that’s difficult, and so rewarding.

“I sat next to a Tibetan rinpoche not long ago. He knew about ten words in English and I knew not a single Tibetan word. According to tradition, sitting near an illumined being allows your mind to calm down and absorb some of that person’s extraordinary quality. If your heart and mind are open, this exchange takes place, language or no language.”

Jacquetta has shared her knowledge of these enduring practices through a long and varied tenure as a “gypsy teacher,” offering lectures and workshops at guilds, museums and university anthropology departments. “Teaching demands high-energy and intense focus,” she says. “Concentrating completely on someone else’s process, fi nding the blockages of their mind and helping to ease those, is enormously rewarding. Seeing people fl ower under your hands is miraculous. Jacquetta has demonstrated this elementary toe loom while waiting at the doctor’s offi ce or at the airport. “I usually gather a few curious bystanders who wonder what the hell I’m doing! It’s another way of teaching.”

“Milton grasped a long time ago that exposure to the arts is essential in developing healthy, balanced, creative human beings. During my lectures and classes, people are dazzled by the sophistication of these ancient techniques. They gain an interest and a respect. I’ve found honorable work in helping to preserve these beautiful and important traditions.”

–Erin E. Berg