A Brief Moment at Milton During the Vietnam Years (1969–1970)

Although known principally as an attorney with a strong sense of social justice, Miles Gersh also served as a remarkable English teacher at Milton Academy in 1969–1970. Fresh from Harvard Law School, he took a “gap year” teaching at Milton while transitioning to his first job in the law as a public defender in Washington, D.C.

I was in 10th grade when Gersh arrived. He quickly made a big impression on his students. In part, we admired him for his remarkable intelligence, his breadth of knowledge, his interest in the larger, public sphere, his integrity, and his amazing eloquence. He spoke in paragraphs without pauses or filler words. Most of his students also responded to his strong liberal politics at a time when the anti-Vietnam War movement swept higher education and many secondary schools.

Gersh was beyond cool. He drove a green MG sports car and showed a sophisticated, broad taste in music encompassing the Band, the Byrds, Beethoven and Bach. It was Gersh who introduced me to the Brandenburg Concertos on period instruments and to Deutsche Grammophon. By the end of his first semester, he was one of the most popular teachers among his students in grades 10–11.

For the many students who admired and loved him, Gersh was far more than a brilliant speaker with an interest in big issues and ideas. He was humble, soft-spoken and a great listener. He displayed unusual kindness and compassion. These personal qualities informed his teaching, which drew not on any specialized academic knowledge but on a lifetime of wide and close reading. He taught Faulkner and Bellow, among others, and was equally adept at traditional and contemporary fiction. His emotional intelligence made him a natural teacher in the old-fashioned sense of a mentor, advisor and friend. Gersh also had a dry sense of humor, which expressed itself in commentary on absurd social and political trends delivered with an incredulous tone punctuated by sudden bursts of laughter. Those explosions and the radiant smile which accompanied them did as much to endear us to him as anything else.

While Gersh was never a manic performer like the boarding school teacher played by Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society, he was just as beloved by his students, just as charismatic (in his more subdued manner), and left just as much of an impact despite his short time with us.

It was easy back then to stop by your favorite teacher’s place, uninvited, and hang out ”shooting the breeze.” With one of my friends, I was a regular visitor at Gersh’s faculty house, which he shared with Milton Smith. We would ask him questions about all manner of subjects just to elicit his marvelous, impromptu summaries of complex issues. We had him play his favorite music so that it might become ours as well. By ourselves, we competed with imitations of Gersh, recited his brilliant summary of Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis (which we had transcribed and memorized), and swapped stories about our latest encounters with our favorite teacher. At the end of the year, we showed up at his house with two whipped cream pies and coated him and Milton Smith. I still have a fuzzy black-and-white photo.

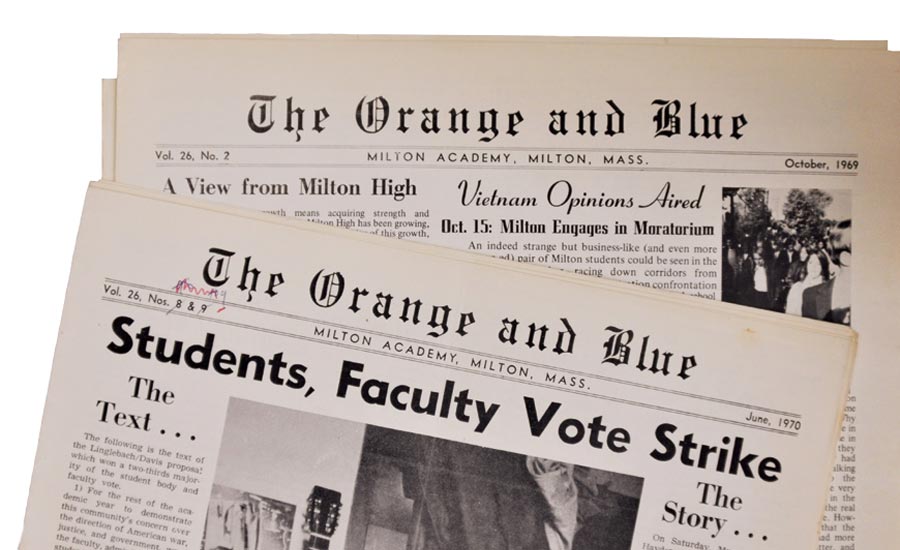

Immediately after the Kent State massacre in early May of 1970, hundreds of universities and colleges went on strike for the remainder of the semester. That night, some 30 Milton students met secretly in the Chapel to plan a strike for our campus as well. Over the next few days, liberal students and some younger faculty organized an all-campus meeting where we voted to suspend classes and concentrate on political discussions, racial and gender awareness, and anti-war efforts. This strike was resisted by the headmaster and many but not all of the older faculty. But it enjoyed strong support among the student body and many of the younger teachers. Among these was Gersh, who spoke up at the all-campus assembly about the need to suspend “business as usual.” Largely because of his popularity and because he dared to speak u

p publicly, Gersh became a convenient scapegoat for some who blamed him for “inflaming” the students. Nothing of the sort took place. The more activist students met privately on their own within 10 hours of the Kent State massacre and planned the strike in the dead of night without faculty input. The fact that the younger teachers eventually supported this plan was a separate development and completely expected given the liberal politics of many younger, upper-middle-class, educated elites at that time. Far from a rabble-rousing radical, Gersh’s characteristic manner was moderation, restraint, and mildness of temperament. At the same time, his strong sense of social justice informed much of who he was—a socially engaged intellectual.

When I was hospitalized in the infirmary for four days after an acute appendicitis, one teacher came to visit me—Miles Gersh. This simple act of charity left a deep impression because it was so characteristic. Having been sent off to boarding school at 13, I missed the two people in my family whom I worshipped: my doctor father and my older brother. Only decades later did I realize why Gersh had been so important back when I was a socially awkward 16-year-old a thousand miles from home. Born 10 years earlier, Gersh was young enough to be like a cool and kind, older brother but old enough to be a father figure. He replaced both of my mentors. I’m sure I was not alone.

After Gersh moved on from Milton, I kept in good touch as long as he remained in D.C. I camped out a number of times in his apartment when passing through and did my best to show him that I had turned out OK after the worst angst of the teen years at Milton. After he moved to Denver, I would call or email out of the blue every five years. He always replied promptly, as if he understood his duties as a Milton teacher extended far beyond his employment or our graduation. When I attended a wedding in Colorado in June 2013, I finally had a chance to see him after almost 40 years. (See attached photo.) I was proud to introduce my wonderful wife and son and to show him that I had done right by myself as a professor. In return, he gave me the approval and affection he knew I had come to receive. His kindness, emotional nuance, and humor were unchanged. I told him I would write him a long letter explaining why he had been so important to me at a time of great personal uncertainty.

Over the next two years, I kept reminding myself to write that letter while we were both alive. When Gersh’s email went silent at my most recent communication in March 2017, I Googled him and found that he had passed away in January 2014, just six months after our get-together. In the immediate aftermath of that shock, I have written this tribute in the hope that death will not swallow up his brief but important contribution to the Milton community. My remarks are too late for Miles … but not for his daughter, Maris, or for his other students.

Robert Baldwin ’72

Associate Professor of Art History

Connecticut College

rwbal@conncoll.edu