Each June for the past 14 years, I have taught at the Harvard Summer Institute on College Admission. For 55 years, the Institute has offered a weeklong, intensive introduction to all things college: the nuts and bolts of writing an effective recommendation; how to help families manage financial aid applications; the role of affirmative action; and what leadership in the college admission profession means, for example. Two of my colleagues on the faculty are high school counselors and 15 are college deans of admission and financial aid. At the end of this year’s program, we talked about the changes we have seen in our years of teaching at the Institute.

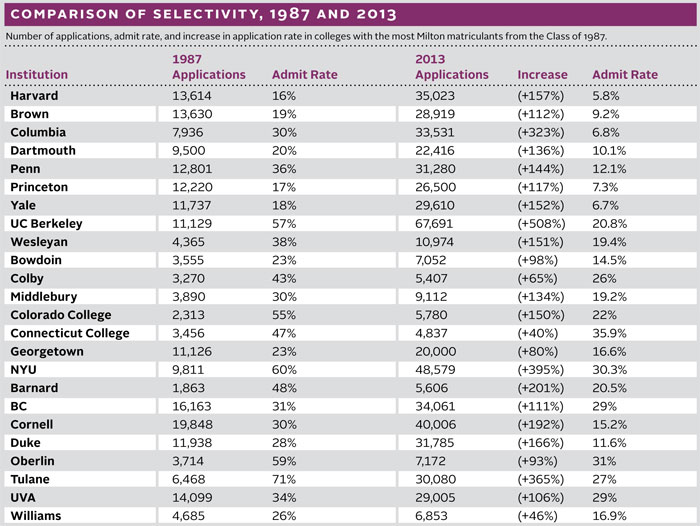

In fundamental ways, little has changed. Yes, each year applications rise and selectivity increases, but the core realities of getting into college persist. Academic performance — the transcript — is paramount. Tests must be taken, applications completed, deadlines met. On the college side, decision making is increasingly difficult. We counselors help students and families manage that core work as thoroughly and thoughtfully as possible, to develop applications that capture each person powerfully, distinctively. Admission officers try to make fair, fully considered evaluations of those applications.

Counselors joke that we are held fully responsible for decisions over which we have little or no control. College admission officers say that institutional and social forces frequently affect how they act on their “read” of each file. Students and schools take their best shot, colleges use their best judgment, and, in the end, “It is,” as Bill Belichick intones, “what it is.”

The most meaningful shift that my co-teachers at the Institute have seen is the increasing anxiety students feel in the encounter between “what it is” and what families and students have dreamed would play out. Each year more Institute participants (nearly two-thirds of the 180 are high school counselors; the balance are college admission officers) have called for sessions that address the health and well-being of students. How do we give students the personal and emotional strength to thrive in the world they face? How do we help them cultivate a strong sense of self that rebounds in an intractable and arbitrary world? How do we make sure that they act with confidence and with heart? We have recently added sessions like “Soft Skills for a Tough World” and “No Normal Is the New Normal,” to address these concerns. These incorporate the latest research on resilience, self-regulation, happiness, growth mindsets, and on the particularities and complexities of forming identity during the college admission process.

Students’ feelings of disempowerment and insecurity are real. When he spoke to Milton students last year, Pulitzer Prize winner Junot Díaz pointed to fear as the primary emotion and motivation in students’ lives — and not for dramatic effect. A faculty member at MIT, Díaz sees around him a state of mind and heart that we all need to confront. During this year’s Institute, preparing for the “Soft Skills” session, I noticed an article called“Big Mother” in the June edition of Boston Magazine. The writer described how “drone-parenting” and the potentially toxic mix of parents’ concerns about their kids’ safety, coupled with unfettered 24/7 access to them, can actually increase anxiety and reduce independence in our children. At the time, I recalled my father-in-law’s parenting philosophy — “We raised you to leave us” — and dove into two recent books about parenting: David Brooks’s book, The Road to Character (he argues for cultivating “eulogy virtues,” not “résumé virtues,” in our children), and Julie Lythcott-Haims’s How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Overparenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success.

Milton’s mission is preparing children for lifelong success; that animates our college counseling program as well. We can significantly affect the emotional and social growth of our students; we can give them the tools to take on the world with gusto, resourcefulness and joy. (One Ivy dean, noting the challenge of selecting from among highly accomplished students, talked about looking for the students who “found joy” in what they did. Will parents now look for “joy” coaches?) In various presentations, I have referred to the IBM study “Capitalizing on Complexity.” IBM asked 1,500 CEOs from around the world which quality they most seek when hiring the next generation of leaders in their industry. Their answer: creativity.

The caution that students should consider, given hyper-selectivity in colleges and a challenging job market, is falling prey to reductionist thinking. Fixating on grades, test scores and “essential” extracurriculars at the expense of developing the whole person leaves that person least able to handle the factors that provoke anxiety in the first place.

In the college office we explicitly focus on the whole person. The dean of admission at Duke once observed, “It’s not about the bumper sticker on the car.” Instead, it is helping students stay loose so that they can relax into their best, most dynamic selves and do their best work. In that scenario, creativity has a chance to thrive. Our college process program involves lots of one-on-one conversations, humor wherever possible, and timely reminders about what is really important in terms of students’ lives. We helped develop Milton’s Senior Transitions program: Seniors meet weekly with an adult to discuss success, sleep, leaving home, time management, and other issues that gain importance in senior year. We use the college essay as an opportunity to talk through the thorny aspects of identity, help students shed self-consciousness and speak in their own voice. If we are successful, not only will our students stand the best chance of distinguishing themselves (Finally, the admission officers smile, a real kid!), they will also leave us as the creative, independent, strong-willed, effective and generous people they are capable of being.

by Rod Skinner ’72

Director of College Counseling