by Vcevy Strekalovsky ’56

Our culture values the practical over the artistic. Arts education is often considered a luxury, outside the base curriculum, yet Harvard’s Howard Gardner shows in his “multiple intelligences” theory that visual and performing arts awaken and engage students, leading to self-esteem and follow-through—transferable effects. Our global competitors seem to understand this dynamic. Business leaders who are liberally educated understand that they are managing much more than the bottom line. Creativity, teamwork, flexibility and problem solving are required in science and technology, where change is continual.

Many of us ’50s alumni still savor the memory of Howard Abell’s and Dick Bassett’s passionate introductions to music and art. At Middlebury I majored in the arts, but a biology course so intrigued me that I thought a medical career might fit. Perhaps with a nudge from Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead, I gravitated toward architecture, as it embodied art, science, and working with people toward tangible solutions. My Russian father (with whom I had grown up painting) demonstrated that an artist can bring much to the technical community: his management of a radar component design team at MIT’s Research Construction Corporation with “outside the box” thinking led to a fast-track process, essential to the war effort. At the University of Pennsylvania, I studied architecture in a program focused on the context of a city in need of renewal, and a school of thought influenced by the Beaux Arts-trained Louis Kahn. To him the “existence will” determined what buildings “wanted to be.” He and his colleagues reinvigorated contemporary design, which, until the 1960s, had been inspired primarily by the Bauhaus, itself a reaction to and reinvention of previous movements. Penn professor Aldo Giurgola once described a continuous cultural spiral alternating between the romantic and the classical.

For Frank Lloyd Wright, the magic of architecture was in the plan, which generated the outcome. Wright suggested that another architect, truly following his thought process, would arrive at a different solution. The irony is that Wright’s colleagues replicated his style, and even graphics. Any initial inspiration, it seems, ultimately gives way to comfortable stylization.

Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts architect, Sir Norman Foster, said his most satisfying creative accomplishment was managing his worldwide offices and controlling the quality of his work—yet always with pen and sketchbook in hand. Much of architectural practice relies on things we never studied in school: managing personnel, sales and marketing, preparing budgets, understanding public bidding regulations, generating coordinated electronic documents, and taking on liabilities. A few architects have the opportunity to design signature buildings, but the emphasis is often on a fashionable statement. The design integrity and timelessness of Aalto’s Baker House at MIT and Kahn’s Kimball Museum in Fort Worth are few and far between. Large development projects usually don’t allow time and fee for thoughtful design, so repetitive solutions and computer-

generated details dominate our landscape.

Most important 20th-century painters avoided predictability, or a comfort zone. Picasso reinvented himself periodically, ignoring the critics. John Graham and Wassily Kandinsky were proponents of the archaic, of the primitive spirit embodied in unadorned expression. Graham (a Ukrainian aristocrat who also reinvented himself) gave voice to the abstract expressionists and cultivated appreciation of African sculpture. Kandinsky traced his development from infatuation with color and natural forms to nonobjective painting, always struggling to retain the “meaning,” or spirit, in the expression. The shapes, lines, values, color temperature and edges retained the spirit of nature for Kandinsky, though not the representation. Cezanne transcended mere representation in his still lifes, and conveyed intense sensuality and abstraction.

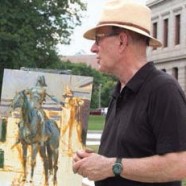

As it is in painting, the satisfaction of architecture for me is the process of problem solving. A project has to work on many levels. Pressure from galleries and the public to paint what sells will always be there; it can lead to stagnation and repetition. Plein air painting excites me because I never know where I will end up; starting with a sketch of the basic idea and trying to maintain that idea as the painting develops is the challenge. Painting from life can have immediacy if the spirit of the subject is retained, its abstract qualities developed, and detail minimized to what the eye (not the camera) sees. I like brushstrokes to show, so that the process and the character of paint are visible. The relationship between lines and shapes in a painting is not unlike that of forms and spaces in a building—the goal should be an interesting visual journey. Though, ultimately, I’d rather that my buildings be painterly than my paintings be architectural.

View Vcevy’s work—both painterly and architectural—at strekalovskyarchitecture.com and strekalovskyart.com.

Post Script is a department that opens windows into the lives and experiences of your fellow Milton alumni. Graduates may author the pieces, or they may react to our interview questions. Opinions, memories, explorations, reactions to political or educational issues are all fair game. We believe you will find your Milton peers informative, provocative and entertaining. Please email us with your reactions and your ideas at cathy_everett@milton.edu