by Jim Connolly, English faculty

Jim Connolly of the English department, who has taught creative writing at Milton since 1983, has long been a poet and writer of fiction. The textbook devoted to teaching poetry that Jim developed is unique in including students’ writing and commentary. He has shared this text with many educators — individual practitioners eager to maximize their effectiveness in the discrete art of understanding teaching and teaching poetry. Jim’s poem, “Comeback,” is included in his recently published collection, Picking Up the Bodies. Jim is now at work on a novel.

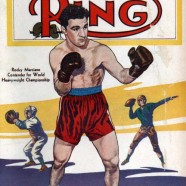

Rocco Francis Marchegiano:

I met him once. He shook my hand,

said “Nice to meet you, kid” and looked

away, money on his mind.

I was with his nephew. I said

“Nice to meet you, champ” and looked

away. I was sixteen,

my own hits and licks on my mind.

Our city’s legend retired

into a dull weight of fame —

overrated, underrated —

and death in 1969,

Newton, Iowa, a mangled plane.

His body flown home to Brockton,

to our family’s funeral home,

my grandfather buried him —

my father, the embalmer, touched him up.

In 1970, I went to Des Moines, Iowa

to teach and met Lowell Coburn,

the young undertaker who shipped Rocky’s corpse

back home to Brockton.

He lived next door. “Nice to meet you,”

he said. “Coincidence is what death can give us.”

And when I returned to Brockton,

a beaten-up place with window grates

on Main Street’s abandoned stores,

the steel defending against the nothing that is left,

I couldn’t find the signs of my

old hometown. At George’s Café,

one of the city’s last landmarks,

I walked through its rooms to study

all the newspaper clippings and photos hanging

on the restaurant’s walls.

I stalked each fight in search

of the city that was gone:

Below Rocky’s photos, Ali snaps a left

through the bloody mouth of Cooper,

and Hagler’s right cross clubs

the “Motor City Cobra’s” chin,

a right, that night, as right as right,

the “Hit Man’s” legs collapsing,

his eyes on queer street,

that bewildered look that takes me

back to the rings and heavy bags

of my youth, all the bad words,

the punches given and taken.

They come back to me like letters

through a chute, the forgotten words

of a boy who learned the lessons

that each fist delivered: fight

to the death, be willing to die

on each street corner,

every win and defeat another notch

in a reputation that tells you

who you are —

I was a dumb kid,

I say to myself, who has grown old and dumb,

neither embarrassed by it nor proud of it —

we were boys who grew up in our fists.

And, today, I wonder what Rocky would say

about The Brockton Enterprise’s front page news,

the heroin addiction infecting our city,

the headlines spreading across the country,

the White House announcing

the match between the government

and the bad batch of stuff

that’s killing our city’s immigrants

in staggering numbers, the newspapers recording

each day’s deaths like judges scoring the rounds

of a one-sided fight.

And I remember my grandfather

chalking the names of the deceased on his blackboard,

the posting of the wakes and funerals.

I stare Rocky down once more.

Hanging high above the other boxers,

his right arm is raised in victory,

and that right hand, famous,

now, and then, is always

coming back to me, heroic

in that night of near defeat against Walcott,

our champ coming back in the thirteenth round,

that right smashing into Jersey Joe’s jaw,

a bullet in a bolt that locks shut —

what we had and can never get back.