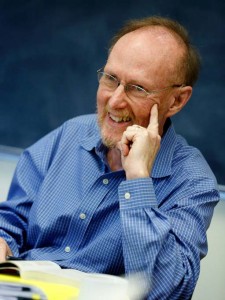

David Smith, English Department

David Smith, English Department

Member of the Faculty, 1981–2015

“Teaching is play, and anyone, at whatever level, who forgets this axiom will probably have a grim time of it,” writes David Smith, in his new book, Be a Teacher: A Memoir in Ten Ideas. After all, he reminds us, “[We are] but sharing a few precious hours with grumpy, cheerful, feisty, querulous, randy, reflective, impulsive, generous, and spirited teenagers, who deserve a full initiation into the human comedy before they go to college, let alone law school.”

As far as I can tell, the best strategy for singing praise to David is to sing using his own words, for he strings them together better than any of us — and what better way to start than to remind us that at the heart of this sweaty work of teaching well must be laughter, to keep the overly earnest, the overly strategic in us at bay, and, most of all, to keep the students around our tables invested in the ride. “For the laughter,” he writes, “more is more. We cannot remind ourselves too often that everything we do totters on the edge of comedy and that comedy is redemptive.”

But, of course, David’s humility would resist my quoting him for all of this, so instead, here goes a too-brief history lesson: In 1981, 34 years ago, and a year before his and Janna’s first child, David came to Milton Academy, kicking off a career so committed and sweeping that my attempt to summarize is, well, laughable. For starters, in only his second year here, David revamped the entire Class IV English curriculum into the course we still teach today, launching his role as architect-in-chief of so much of our department’s offerings: the classes Expo, Performing, and the Craft of Nonfiction, notably. Nearly a third of his tenure here, he served as department chair, anchoring and guiding us with deep generosity and steady diligence. Hunkered down at his desk, hard at work before the morning doors are unlocked and long after his junior colleagues have limped home, he has always set the work-ethic gold standard.

And David has taught our curriculum across every level, even middle schoolers back in the day, an age he missed for its wild energy and its requirement of play — such as the time, he recalls in his memoir, he entered the class, to the great applause of his students, out from underneath the Harkness table. For even our Lower School students, he was, for decades, the chess guru, teaching them strategy and cheering on their checkmates. In the last few weeks, Upper School students, current and graduates, have written, eager to help me with this encomium. One marvels at David’s ability to provoke the class with the right questions: “We were no longer talking about Emily Dickinson; we were talking about accepting death. We were no longer evaluating Huck Finn’s role in society; we were debating the merits and drawbacks of conformity.” Other students note his literary expertise: “I can only hope to someday know as much about a subject as Mr. Smith knows about literature,” one writes. Another: “Even though I’m now halfway done with [college], my favorite and best-taught class of all time is still undoubtedly David Smith’s two-year English. The class began with Mr. Smith reciting the opening lines of Beowulf in Old English, in a rolling Anglo Saxon cadence, guttural and elegant. Mr. Smith not only improved my writing immensely, but he made me love the writers he taught — John Donne, Samuel Johnson, Jonathan Swift.”

Repeatedly, his students describe his egolessness, his goal to — as he says — “step nimbly out of the way” and let them drive the conversation, a goal rooted in David’s suspicion of a teacher’s crowning himself king of the classroom. “Students hold ultimate authority,” he argues in his memoir. First, “after you are gone they will still be here, bull-headedly making the mistakes you warned them against and otherwise flouting the brilliant lessons that you spent so much time preparing for them.” He continues, “The second reason . . . goes straight to the philosophical core of the business: The mind is and must remain free. As soon as we forget this principle, we have given up teaching and begun indoctrinating.”

The mind must remain free: clarity as political as it is philosophical. Perhaps my favorite thing about David is just this: his activist spirit, his will to protect, perhaps most of all, honest human exchange, knowing that classrooms and schools and countries maintain their integrity by ensuring that all people have a voice at the table. He has taught so many of us here to stand up for such ideals, to argue them with conviction. Think of our Faculty Council as his legacy, the result of his efforts to organize and empower our faculty voice. But just as powerfully, David has taught us the art of listening, that change is forged through connection, that our ability to be moved by each other is a critical measure of our freedom.

One evening this spring, I sat talking with David about his career here at Milton — one he wouldn’t exchange for any other. He mentioned that he hopes his teaching “creates a space for his students to occupy” — a fitting metaphor, it seems to me, for the position we all now find ourselves in. We’ve reaped his wisdom, and he’s had plenty of time with our “grumpy, feisty, impulsive, spirited” selves. On blue days, I’m not quite sure how we’ll manage without our teacher. On brighter days, though, I imagine him leaning back in his chair, away from the table, smiling gently — certain he’s given us all we need, and wishing, for God’s sake, that we’d just occupy! It’s our turn, after all. But don’t — he might add, before slipping “nimbly” out the door — take yourselves too seriously.

by Lisa Baker

English Department Faculty