Pulling on the signature white coat every morning, ensconced in a Yale genetics lab, Althea Grant ’89 could have congratulated herself: her scientific career was right on track. Yet, she was not happy. More than fifteen years later, Althea wears a khaki Public Health Service uniform to her office at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta. Now, she is right where she wants to be. Soul searching, networking and research helped Althea devise and embark on an unusual, even unlikely career shift from a coveted role in lab science to service leadership in public health. Today she brings that same inventiveness and drive to the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. She is acting director of the Division of Blood Disorders, and her particular focus is sickle cell disease.

“The answers to the questions we deal with in public health are not straightforward,” Althea says.

“The answers to the questions we deal with in public health are not straightforward,” Althea says.

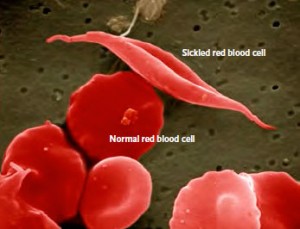

She hasn’t left hard science behind. On her busy Twitter feed (@DrGrantCDC), Althea describes herself: “disease detective, scientist, passionate about public health.” Her first project as head of epidemiology for the Centers’ Division of Blood Disorders: how to collect population data on sickle cell disease (SCD). Characterized by C-shaped red blood cells, sickle cell can lead to chronic pain, strokes and infections. Roughly 100,000 people, primarily African Americans and, to a lesser extent, Latinos and other racial and ethnic groups, are diagnosed with the condition. Beyond that number, however, little data existed on where those who are diagnosed live or how they get services.

Althea’s vision—to establish a new national registry that would collect valuable data—was impossible without new funding. Months of meetings, travel and study helped her craft a program to gather vital information about sickle cell disease.

In 2010, the CDC, along with the National Institutes of Health, launched a pilot program in seven states called RuSH—the Registry and Surveillance System for Hemoglobinopathies—to collect population-based data on people with SCD and thalassemia, another blood disorder.

“I took on that goal and worked it,” Althea says. “Getting funding for a completely new project forced me to be more resourceful than I might have been.”

The daughter of two postal workers, Althea grew up in Newark, New Jersey. She didn’t excel in music or the visual arts. Not quite five feet tall, she wasn’t likely to be a star athlete, either. Math was a strong point, and though she wrote poetry too, Althea gravitated to the sciences. With two generations pushing her to excel—her grandparents lived nearby—Althea found Milton through A Better Chance, a program that connects outstanding students with opportunities beyond those that the challenged schools near home could provide.

“Being at Milton put me on a particular trajectory,” says Althea. “I was really well-positioned to go anywhere I wanted to go.”

After Milton, Rutgers welcomed her home. The first in her family to earn a college degree, Althea received her bachelor’s in biochemistry. She enjoyed science, and it also felt like a path to a solid career. That was important to her. In hindsight, she thinks she chose science because it felt less risky than writing or studying in the humanities.

“Science seemed more unequivocal,” she says. “You got the answer or you didn’t. There was less room for subjectivity in people’s critiques. It felt like a safe place to go.”

After earning her Ph.D. at Emory University, she pursued a postdoc in biochemistry and came back north to Yale. Her mentors at Yale were great, and her research into yeast, a model for human genetics, was going well. But something was wrong.

“Though professionally, everything was going fine,” Althea says, “I thought I had lost my mind.”

Althea had never questioned her commitment to science, and she had invested years of education in a lab career. Now she was faced with figuring out where she really wanted to be and how to get there. So she started a new research project—into a career change. She began by trying to remember a time when she felt passionate about her work. The feeling of engagement that she had during her public health classes came to mind. After watching several family members suffer from HIV, she also

Althea had never questioned her commitment to science, and she had invested years of education in a lab career. Now she was faced with figuring out where she really wanted to be and how to get there. So she started a new research project—into a career change. She began by trying to remember a time when she felt passionate about her work. The feeling of engagement that she had during her public health classes came to mind. After watching several family members suffer from HIV, she also

felt a growing urge to serve.

All of that led Althea back to Atlanta. She wanted to become an epidemiologist, and she set her sights high: the CDC. She was aware that, in major ways, she was starting over. Federal government jobs in the field were notoriously hard to get. Althea was aiming for the most prestigious public-health institution in the country. She relied on her science skills and reputation to get a head start. She targeted and won a fellowship in the Mycotic Diseases Branch, where scientists study fungal diseases like yeast infections.

“I thought, I can convince them that I can do fungus, and I’ll be doing fungus at the CDC,” she says. ”Once at the CDC, I will learn and network and go back to school and do all these things to move into the field I want.”

That was her strategy. Her career path took years and led to several different branches of the agency before she arrived at the Division of Blood Disorders. That division felt like a perfect match. Blood Disorders has a research lab, and the diseases are mostly hereditary, so her genetics background is an advantage.

“Creating an opportunity to come here, to speak the language and to synergize my own skill sets meant figuring out a unique pathway,” she says. “When I finally reached the division, there was no funding for the things that I felt were most important.”

The division was focused on hemophilia, but Althea saw a significant gap in public health action on sickle cell disease. So she started talking to patients, other branches of the CDC, and to the National Institutes of Health to win support for the idea. She went to every relevant meeting she could think of—from academic research sessions, to staff meetings at the National Institutes of Health, to gatherings of the patients and doctors, to community-based organizations like the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America. She traveled frequently and did much of the networking on her own time. Althea started her family while her eyes were focused on this public health goal. She now has four children, and when they were young she sometimes took them along to meetings.

Not only did she succeed at securing the funding to launch. Althea is working to expand sickle cell screening in Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya. She’s working with the World Health Organization and other organizations to add more developing countries to that list. The work on sickle cell earned Althea a prestigious Public Health Service Commendation medal, represented by a number of colorful stripes on her uniform.

Last year, widespread federal budget cuts in medical research hit the RuSH program. Its four-year running time was narrowed to two, and the program ended in 2012. Now Althea is concentrating again on figuring out how to make something important happen, against the tide. She’s ready for it. “If I don’t do this, no one will,” she says. “I’m not a placeholder. I need to be a leader and a driver, and that’s a unique opportunity.”

— Tinker Ready