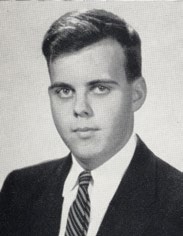

During the last half-century, both Milton Academy and Harvard University have counted on a single alumnus—Jack Reardon, Milton 1956 and Harvard 1960—to be alert at the hub, both hubs. Jack has profoundly influenced the recent histories of both schools at the infrastructure level. He has affected fundamentals: issues that determine what these institutions can achieve; how they can weather danger and damage; and how aggressively they can or should aspire to new goals. Reliably congenial, Jack is also rigorously attentive to standards. More aware than most people about what might be practical or impractical, he nonetheless always asks, “What’s right”? A student during the 1950s, he has guided two rooted and resilient institutions across old boundaries to adopt and even embrace change. “I’ve always been able to do different things in different areas, and was able to make a difference, I think,” says Jack, “with individuals, mostly.”

Having earned his M.B.A. from the Wharton School at Penn after Harvard, Jack had a real political experience at the center of the dynamic Boston Redevelopment Authority as Boston approached large-scale urban renewal. Jack was hired by Ed Logue, who was development administrator, and he was to report to Kane Simonian, who was tenured and held the titles of executive director and secretary of the authority. The political situation at that time meant that these two men did not work well together. While Jack was not able to change the relationship, he says that both men gave him a positive experience, and they remained Jack’s friends for life.

While at the Authority, Jack would also visit local schools for Harvard admissions, already interested in students’ lives and their options for the future. When Fred Glimp invited Jack to join Harvard’s admissions staff in 1965, at an annual salary of $9,000, Jack reasoned, “If I didn’t accept the job, I’d probably always make just a bit too much money to be able to live on that income.” His decision to join Harvard’s staff launched 12 years of work based in the admissions office, but not limited to it. “I lived in the yard and proctored,” Jack says, “then became residential dean at Kirkland House. I enjoyed it all.”

“Jack goes five steps beyond the call of duty,” says Bill Fitzsimmons, who joined Jack in the admissions office in 1972, and is now Harvard’s dean of admissions and financial aid. “Jack took it upon himself to know every single person well, especially in Kirkland House. He’d sit down with students. He’d counsel them: “What makes the most sense for you right now? What next steps would make the most of who you are and what your talents in life are?”

“Jack always had a preference for those groups who had lost hope, either racially or economically,” says Michael Murr, Harvard Class of 1973 and key financial supporter for Harvard, “people not typically touched by the mainstream opportunities.”

As an orphaned high school senior and a football player, Michael Murr lived in Walla Walla, Washington. His eyes were trained on playing in a Pacific–8 school. Harvard was far outside his frame of reference when some alumni brought it to his attention. Michael remembers that Jack met him at Logan, toured Harvard with him, ushered him into a class and into a conversation with coaching staff. Michael wasn’t persuaded. Giving up his option to play at a Pac–8 school to undertake something as distant and unfamiliar as Harvard was not appealing. He turned Harvard down and then reconsidered at the last minute, just before school opened. When Michael arrived at Harvard, Jack was his freshman advisor. “I was concerned that I wasn’t prepared for Harvard.” Michael says, “Jack convinced me that not only would I be okay, but that I would excel. I had been living on my own since I was 16, and Jack inspired such confidence in me. As he is about nearly everything, Jack was right.”

After five years in admissions, Jack and a number of others became convinced that Harvard’s financial position would support funding a greater number of nontraditional candidates. Jack remembers their long conversations, in 1970, late into the evening, with Chase Peterson, then dean of admissions and financial aid, on being more intentional about enrolling some of these students. “The dean agreed with us that we needed to do a lot more, and right away,” Jack says, “and we moved on that.” Soon, Jack was leading others in that effort: in 1971 he became director and in 1975 associate dean of admissions and financial aid. During this time, Harvard and Radcliffe integrated separate admissions operations.

Jack’s skills were already on tap beyond the admissions office. Bill Fitzsimmons points out that Jack served as a “bridge to Boston,” a critical person in the relationship between Harvard and Boston over many years. When Chase Peterson moved from admissions to become Harvard’s first vice president of alumni affairs and development, he relied on Jack to “help me think through that office.”

Listening as closely as he did to students, Jack became increasingly aware of how urgently Harvard athletics needed attention. Athletic facilities were outdated and insufficient, a reality gaining definition as Harvard absorbed the Radcliffe athletic program, and across the university, interest in physical exercise grew.

The athletic director’s position opened up during the fall of 1976, and Jack was interested. Although Jack calls himself “a controversial candidate” because he’d never played college sports, President Derek Bok appointed him director of athletics in September 1977. At that point, Jack had already positioned Harvard athletics for major change—with a master plan as well as philanthropic support. In February 1974, President Bok and the Harvard Corporation had given Jack approval to prepare plans, and in June of that year Chase Peterson had appointed him to a special fund-raising effort directed toward the athletics plant.

Always a great fan, Jack shares his enthusiasm for Harvard football with Drew Faust, president of the university.

Summarizing 13 years at the head of athletics, Jack says, “We built lots of buildings, there weren’t any scandals, and teams did relatively well.” The detail is more substantial. In his book Crimson in Triumph, A Pictorial History of Harvard Athletics 1852–1985, Joe Bertagna describes Jack as a singular character who was able to develop a plan to meet the athletic needs, win approval, identify the key donors, and execute the plan itself. On May 15, 1976, ground was broken and “by 1985, Harvard’s entire athletic plan had been affected by the change,” which totaled $32.5 million. Intercollegiate athletes, house teams, and recreational athletes all benefited from these advances over less than a decade.

During Jack’s tenure, the department spearheaded a cultural shift toward recognizing female athletes appropriately—a transition no smoother than those at other universities, but a steady and deliberate one. Incentivized by Title IX (1972), Harvard added a dozen sports beyond those offered at Radcliffe and increased the budget more than tenfold. By 1984, Bertagna cites “nearly 600 women competing on 33 teams in 18 intercollegiate sports…another 1,000 on intramurals, as well as post-season opportunities comparable to those the men enjoyed.”

Bill Cleary, who followed Jack as Harvard’s athletic director, says, “I was fortunate to inherit the nation’s largest Division I athletics program, and as far as I’m concerned Jack was its architect. We had 41 varsity sports at the time, along with junior varsity and club teams. Jack grew those programs for students; he had a tremendous feel for students, and for coaches, too. I put Jack on every committee that had an important coaching decision at stake, and I’m sure Jack is just as critical for Bob Scalise (current athletic director) as he was for me. I think one of the great joys of Jack’s life is having been so involved in athletics.”

A few years after Jack helped manage Harvard’s 350th anniversary in 1986, Fred Glimp, vice president for alumni affairs and development, and President Bok suggested that Jack consider directing alumni affairs. Since 1990, Jack has led the Harvard Alumni Association, connecting the university with all its alumni, in the United States and around the world. Jack’s brother, Tom Reardon, was leading the university’s development effort at the time. Their synergy, integrating the planning and the goals for alumni and development, turned out to be a key strategic strength for Harvard.

Jack serves as associate vice president of university relations as well, working with Tamara Rogers, current vice president for alumni affairs and development; Drew Faust, president; and the board of overseers. Jack staffs the alumni committee responsible for nominating candidates for the Harvard Board of Overseers, the larger of Harvard’s two governing boards. The committee reviews hundreds of potential nominees to name eight candidates, who run for five places and serve for six years. The board meets five times a year; Jack attends the meetings and also works closely with individual overseers. The nomination process itself, as well as service on the board, is a great crucible to identify skilled, dedicated leaders who will help determine the university’s direction. Men and women elected to the corporation (the smaller governing body formally known as the President and Fellows of Harvard College) have often served terms as overseers first.

Jack is able to “get key people energized,” Tom notes, building connections that lead to volunteerism at Harvard over years, to philanthropy that changes the quality of the undergraduate experience, and in certain cases, to pivotal leadership roles, helping shape Harvard’s future. “Jack has the best judgment, the best character, and the keenest institutional sense of anyone I have ever known,” says Tamara Rogers. “He is both an optimist and a realist who inspires trust. I have learned immeasurably from him and I admire him more than I can say.”

“Jack subordinates his own ego to serve others and the institution,” Michael Murr says. “He has a role in so many important decisions and you rarely see his hand. It’s fascinating to watch Jack in the middle of epic battles. His connections in the community are so deep, his moral compass is so strong, that most people shudder at the prospect of crossing Jack.”

“There are few people at Harvard, over a very long tenure, who have not sought and benefited from Jack’s wisdom and candor,” Bill Fitzsimmons says. “His ability to be the best kind of devil’s advocate allows you to think through all sides of an issue.”

Jack’s Harvard template applies seamlessly to Milton’s history during his 22-year tenure on the board. While Milton’s context is distinct, Jack’s skill and unique sense of responsibility influenced the course of events at Milton again and again. The scale may have been different, but Jack’s impact was equally defining.

His opening trustee project was helping Milton undertake a first comprehensive capital campaign. Peer schools had long ago focused on building endowments that fund annual operations, and making facilities improvements that support top-notch education. Jack helped trustees and administrators understand what needed to be done, commit to a level of fund raising new to Milton, and succeed together. He chaired the steering committee charged with setting the goals, organizing the leaders to meet the need, and launching the drive. Beyond raising $60 million from 1995–2000, “The Challenge to Lead” expanded the strong, supportive connections with alumni and parents that would be a crucial foundation for future planning and capability.

Once the campaign was underway, the Milton board addressed other key questions. Competing priorities, institutional traditions, strong opinions, and finite resources all complicated the decision-making process. Should Milton build a new athletic center? How and when should renovations update the academic spaces? Can we increase the diversity on the board? Will we be well prepared if we decide to rebalance the boarding and day student enrollment at Milton? Are we connecting with young alumni effectively? Predictably, Jack helped people hear one another, confront reality, and agree on a direction and action steps.

Jack often figured in the foreground—leading an assessment of students’ experiences in athletics, for instance, or expanding the numbers and influence of women on the board. He was just as likely, however, to be active in the background—providing counsel to the board president, or testing faculty opinion about an issue at stake. His reputation as a listener qualified him for many tasks a less courageous person would deflect. People sought his perspective, privately and publicly; it was reliably candid and tactful at the same time. “I’m pretty straightforward,” Jack says. “I’ve been honest with people.”

In June 2007, President of the Board Fritz Hobbs turned to Jack with the prospect of identifying Milton’s 12th head of school. Along with his co-chair Vicky Graham, Jack mapped out a search process that would seek and consider opinions from every Milton constituency—faculty and staff, students, alumni and parents—across the country and internationally. He traveled for Milton, assuring Milton audiences that he wanted to know their perspectives as well as their hopes. “We want everyone who has an opinion to feel that he or she has had a good opportunity to share it with us—in person, online, over the phone, through the mail.”

“Jack’s assurance about Milton’s strength and excellence and endurance was critical for me at that time,” says Todd Bland, current head of school, “especially when he and Vicky had to restart the search, after one finalist withdrew early in 2008. That conversation with Jack allowed me to keep my eye trained on Milton and the chance to lead the School.”

After seven years leading Milton’s board, when Fritz Hobbs began to consider his transition, Jack was again the right person to develop consensus about new leadership. For Brad Bloom, who accepted a nomination to serve as president, Jack’s inspiring persuasiveness was rooted not only in his institutional wisdom, but in the many hours Brad knew Jack had devoted to gathering thoughts from each board member. The board elected Brad Bloom as president in 2010, at yet another pivotal and promising time in Milton history.

Why give back, at this level, to demanding institutions, over many, many years? Jack says that his affection for Harvard is “an innate part of me. I really love this place.

“Everything about Milton was good to me, as well,” he says. “I enjoyed many of my teachers. I learned from Stokie, who always knew what a bad athlete I was, about the importance of being organized and being efficient. When I lost my father, the summer after seventh grade, Frank Millet worried about me, and I thought then that he was tough with me. Frank often paid attention without your knowing.”

Frank Millet remembers Jack at Milton as “a perfectly decent person with a lot of friends.” Just this past June, Frank said “Jack is good at giving people advice; he’s nice, and not overbearing. We’ve always been good friends—I may have been the only Catholic teacher he met. He has a good sense of humor, and he enjoys people.”

Progress in Jack’s world depends on expertise—artistry, even—in managing “process.” Few people are skilled and even fewer are patient enough to guide the conversational commerce within or among groups that successfully heals institutional wounds, or tackles intractable problems, or determines successors for key positions. “He’s developed skills based on a core set of attributes,” Tom Reardon explains, “gaining an understanding, respecting, reconsidering an opinion. So in difficult situations, Jack may be able to move things forward. He doesn’t try to camouflage and he isn’t antagonistic or insulting. At the core Jack’s focus is on people, on human beings.”

“He has never been about prestige, or money, or even some dry sense of ‘community,’” Bill Fitzsimmons says, “and he has strengthened both Harvard and Milton immeasurably.”

–-Cathleen Everett