A progressive idea among friends from the ’5os penetrates students’ lives today.

Two weeks after the cataclysmic events of September 11, 2001, a group of friends met to begin planning their 50th Milton Reunion. From their school days in the ’50s through the turn of the century, they had all ably tended families and careers. Now they struggled with a new, incomprehensible chapter.

Ned Felton, the boys’ head monitor in 1952, was sure that these friends could and should organize around an idea. “Ned was sure that we could identify a common project, memorialize our class, and help—in our small way—to make the world a better place,” classmate Jim Fitzgibbons said.

Ultimately they succeeded, in a way that may not have been predicted. The Class of 1952 set in motion a speaker series on religious pluralism, now in its tenth year. Further, members of the class took up their own challenge. The founders identified and brought seminal movers, shakers and thinkers to campus, each year.

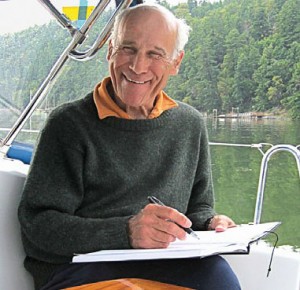

Steve Swett ’52

These challenging speakers annually prod an audience far more diverse than the class itself, to engage. Student newspapers argue, faculty opine, and advisor groups explore—before, during and after these visits. Year after year, members of the class return to campus at 9:15 a.m. on a given Wednesday, to join students and faculty in mind-expanding experiences.

The idea that a group of graduates from the “tranquil” 1950s would execute such a bold plan holds a certain irony. Steve Swett points out that thinking people everywhere were searching for the right response to the events of 9/11. Everyone in the class wanted to be constructive. Steve says his classmates were wondering about an initiative “that would be peaceful, purposeful, and enduring.” According to Steve and others in his class, Ned Felton surfaced the idea to explore religious diversity throughout the country and the world. Not everyone agreed. Steve himself had reservations; he was more an observer than a proponent. Ultimately, Ned’s personal influence was great enough to mobilize this idea that would break new ground. “Acting together to bring an idea to life requires trust, and the perception of shared values,” Steve says. Why did so many in the class trust Ned, and for so long? What kind of a friend was he?

“Acceptance is key here,” Steve explains. “A friend accepts others for who they are; a friend does not have an agenda to impose. Ned was that way. Others might create a sense of awe, or amusement or intimidation; Ned created a sense of affinity.”

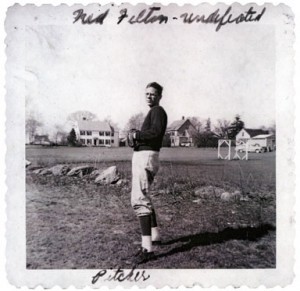

Ned Felton, Class IV pitcher, spring 1949

Prep-school students in the 1950s were homogeneous, put simply. Still, among its peers, Milton was known then—as it is now—for nurturing a broad range of individual personalities. “We all liked people who were interested in more than one thing,” Jim Fitzgibbons explains, “athletes who were also actors, debaters who played instruments. We had more choices in developing friends. No matter who you were you could bring together a group of friends that would feel good. Ned was in the middle of it all and had many friends.”

“I was an athlete who loved the arts,” Bonnie Gardner says. “That interest was probably what connected my closest friends and me for years after Milton. Sarah [Garrison] played the cello; Kitty [Benton] played the violin; I played the piano; Kitty [Hok] played the flute; and my closest friend, Jean Valentine, is a poet. I love that Milton so accepted and encouraged those different interests. “Jean McCauley always arranged for Bob Freeman to play the oboe with us in a chamber group. He was never teased about these sessions. At Milton, you were accepted immediately for whatever you did.”

Demonstrating competence in your chosen interest was a factor, and Ned was skilled at his sport. Steve shares a photo of Ned as a Class IV pitcher on Frank Millet’s Warren Hall team. Steve had written “undefeated” over the 1949 photo of Ned, about to deliver his pitch.

“A friend cares about others,” Steve points out, thinking through Ned’s persona. “He wants people to do well; he’s pleased when things work out for them, and feels badly when they don’t.”

In the journal he kept at Milton, Steve wrote on January 9, 1952, about a Chapel talk Ned had just given as head monitor. Steve wrote: Ned gave an excellent Chapel talk, along the “Dare to be true” lines: don’t be cynical or critical! “In words and deeds, Ned encouraged the high road, and attracted believers.”

Jim Fitzgibbons ’52

Bonnie noted that although they dated in high school, she was “always in trouble” and Ned was “more interested in being a leader.” She remembers that he wasn’t among the boys and girls that occasionally raided the Hathaway House kitchen together, having great fun with otherwise inaccessible “barrels” of peanut butter, sardines and crackers, out of the housemother’s earshot.

“Ned was quiet and serious,” among a group of roommates with robust personalities, Jim remembers of their Harvard years. To some degree, he may have been working out his own identity and role, vis-à-vis his large, lively and prominent Boston family. “I don’t remember Ned as particularly competitive, outside of baseball,” says Jim. “I don’t remember his being very religious, either. None of us were.”

At Harvard, Ned majored in American history. “The learning experience at Milton and the exposure to the liberal arts curriculum at Harvard provided me with a continuing curiosity about things international, which I carry on today,” Ned wrote in his Milton 50th Reunion book.

He volunteered for the draft, but was rejected because of his eyesight. Although it was then August, the University of Virginia “had just started the Darden Business School, and needed Yankees to balance its student body. I was the lucky beneficiary of an effort at diversity in 1956,” Ned wrote.

He met and married Molly McBride, soon had “three wonderful daughters,” and joined the international division of Morgan Guaranty Trust Company.

Moving away from Boston, even to New York, was more than unconventional in Ned’s family’s eyes. The couple began to chart a singular course for their family. “My parents are products of the ’50s,” Ned’s daughter Sarah (’79) says, “but both were fascinated by cultural differences in the world.”

They moved to Brussels when their youngest was nine-months-old, beginning what Molly describes as a wonderful and wild time. The Feltons lived in Europe for ten years, with intervening years in Princeton and then New York. Ned began with Morgan’s business in Europe and Canada, but by 1973 was put in charge of Morgan’s business in the Middle East and Africa. At the height of the oil crisis in the United States, Ned concentrated solely on the Middle East for Morgan.

“The highlight…proved to be our five years in London, when I was seconded to be the first CEO of Saudi International Bank,” Ned noted. “This was part of a 15-year period when I was involved in banking business in the Arab world.” Ned, and often Molly, traveled extensively during these years, and he continued to retain an interest in the Middle East. He replicated his role with the Saudi bank when a group of Kuwaitis were interested in establishing a bank in New York City. He then moved on to head the Bank of Bermuda New York for the last years before retirement. “I found the shocking events of September 11 particularly disturbing because I have known so many fine people of the Islamic faith,” Ned wrote.

Ned’s daughter Sarah, Milton Class of 1979, considers her dad as someone who did not close himself off from change as he grew older. “When things made him uncomfortable, he tried to explore what that meant, and why,” she says.

“He had an evenness about him. People had the sense that he didn’t judge them. As his daughter, I felt I could go to him and have a conversation about the changes in my life. He always listened, and was very thoughtful in how he responded. That said, he was a real person, and we’re all human. He, too, had his black-and-white side.”

Bonnie Gardner ’52

Both Sarah and Molly describe Ned as absolutely devastated by September 11. “He worked and lived in New York,” says Sarah. “He spent so much time in the Middle East. A close business colleague from his days working on the Kuwaiti bank died in the towers. My dad had a strong sense of the diversity in the world, and he knew what it meant to be a spiritual person.” David Morse ’52 pointed out that in Stonington, Maine, where Ned and Molly retired, “Ned had long and quiet winter months, and no doubt did lots of thinking.”

“My mom and dad maintained friendships over all these years that absolutely blow me away,” Sarah says. It’s true that many families linked to Milton in the ’50s were also woven together in a vast network of siblings and cousins, parents, shared uncles, aunts and grandparents. Marriages expanded or deepened the links. The Class of 1952 boasts three marriages, despite the fact that the Milton Academy Boys’ School and Milton Academy Girls’ School were two very separate endeavors in that period. Certainly, New England was home base—sailors and bankers tended to see one another as family members, professional colleagues and competitors on the water. “It was a small world, our world,” says Bonnie.

“That class had a base for what could, or just as easily could not, have worked out as friendships over the years,” Ned’s wife Molly notes. Dynamics could have shifted as classmates found spouses, for instance. Marriages can make simpler relationships more complex, and the opposite, too. Husbands and wives were warmly and immediately embraced. Loyalty and support, those venerable attributes of friendship, thrived, and still thrive.

The people who took seats around the planning table in October 2001 shared, on some level, 53 years of experience. Some, as David Lee ’52, Ned’s second cousin, points out, had been together since the sandbox. Yet the opinions around the room spanned the gamut. The idea that Ned proposed—a purposeful, progressive effort to expand everyone’s appreciation of difference, particularly for young people in their formative years—was consistent with his style.

“Ned’s values were articulated by inference,” Steve says. “He did not wear them on his sleeve.” Nevertheless, as David Lee says, “Once Ned became interested in an idea, he became passionate about it. He thought that misunderstanding about religions was at the root of many of the world’s problems.”

The Friendship Oak from the Class of ’52 As his 80th birthday approached, Steve Swett ’52 made a request of friends who might have considered a gift for him: plant an oak tree, somewhere, instead. Classmate Dan Pierce’s idea, planting an oak in front of Forbes House, came to pass. The tree is named “The Friendship Oak.” At the dedication, after a celebratory watering, friends from the class joined Frank Millet for a luncheon on campus. Dan Pierce, left. Steve Swett, right.

Bonnie Gardner agreed with Ned, and supported his proposal in the most tangible way: Bonnie had pursued her interest in the religions of the world for years. She was ready with a roster of potential well-known speakers and the connections to them. Bonnie had studied with Dr. Dorothy Austin, now at Harvard, when Dr. Austin was a professor at Drew University. Through Dr. Austin, Bonnie was familiar with Diana Eck, founder of the Pluralism Project at Harvard. Bonnie’s exploration connected her with many prominent religious thinkers, writers and academics. She was ready to help bring some of these people to the Milton campus.

Gifts from a number of men and women from the Class of 1952 endowed the series, and a core group defined the series’ mission explicitly. Bonnie and Ned worked as a team to identify and secure each lecturer. Author and reporter James Carroll was their choice to launch the series; Mr. Carroll shared his own examination of religion in October 2002. Ned Felton died in February 2010, and this past December, Molly and Sarah joined the steadily growing number from ’52 in the audience. They listened as PBS journalist and author Ray Suarez gave the tenth lecture in the series. Classmate Judy Millon was particularly helpful in making Ray Suarez’s visit possible. Over the coming year, Bonnie and Judy will shift the lead role for implementing the series’ now well-established mission from the class to the School. “The need to understand the role of the world’s religions,” classmate Dan Pierce says, “has only increased in relevance over the years since the series began.”

As they plan to celebrate another decade as classmates—at their 60th Reunion this June—the Class of 1952 can rely on rich experience, both in understanding and honoring the endurance of friendship.

— Cathleen D. Everett