Poet Robert Pinsky on Translating Dante’s Inferno

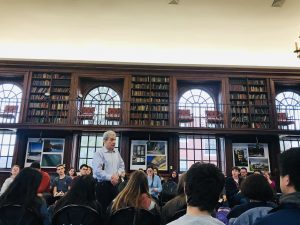

Three-term U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky discussed his translation of Dante’s Inferno last winter with students taking “Founding Voices: Literature from the Ancient World through the Renaissance.”

Three-term U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky discussed his translation of Dante’s Inferno last winter with students taking “Founding Voices: Literature from the Ancient World through the Renaissance.”

In a free-flowing conversation, an affable Pinsky answered students’ questions about his translation, which they were reading in class. He explained that his full translation came about after he was invited to translate one of the Inferno cantos for an anthology. He also helped another poet with his assigned canto and realized how much he enjoyed the work.

“I’m very interested in difficulty—a worthy difficulty—not trivial or canned,” Pinsky said. “I realized with this, I had a difficulty that I really loved.”

The full translation took a year of work and then another year of showing his work to colleagues and Italian friends. “You can’t translate Italian sounds into English; you have to find an equivalent,” Pinsky said. “So if a word sounds great in Italian, you have to find a word that sounds great in English.”

When asked by a student if he ever had to compromise, Pinsky laughed and said he had two answers: “Absolutely never. And every second.” He also discussed the challenge of translating poetry lines from a language that has many more syllables than English does. In order to run the two translations side-by-side in the book, the English translation was “padded” with white space.

Pinsky read aloud Canto 32 and then exclaimed, “Clearly, Dante knows how to tell a story, and it’s an outrageous story!” He talked about the act of reading: “Ideally, you want to read with your mouth and ears, feel it, and get to know it. It’s like listening to a song that you like for the first time. You are not really paying attention to the words but just listening and enjoying the music. Then, on the second or third listen, you might pay more attention to the words.”

Pinsky is a professor of English and creative writing in the graduate writing program at Boston University. His anthology The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems 1966-1996 was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. His work has earned him the PEN/Voelcker Award, the William Carlos Williams Prize, the Lenore Marshall Prize, Italy’s Premio Capri, the Korean Manhae Award, and the Harold Washington Award from the City of Chicago, among other accolades.