Born To Lead

-Shortly after her appointment to her new post, Physician and chief medical officer Meika Neblett ’90 was confronted with one of the worst health crises in a century.-

“Everything I did was in preparation to be the doctor I wanted to be,” she says from her office at Community Medical Center, in Toms River, New Jersey, where she has served as chief medical officer for the past year.

Her determination and certainty about the future kept her life on track and busy after Milton: She earned her bachelor’s degree from Emory University in three and a half years, spent a summer studying Spanish in Mexico, earned a medical degree from Howard University, and completed a three-year residency in emergency medicine. In her freshman year at Emory, she also made time to play varsity tennis and competed that year in the Women’s NCAA Division I Tennis Championship.

Meika Neblett – Chief Medical Officer at Community Medical Center and Southern Regional Medical Director RWJBarnabas Health

But what she also knew from an early age was that she wanted to play a leadership role in her profession. “I like being part of decision-making and understanding exactly why decisions are being made,” she says. “I’m good at pulling together tons of different opinions and formulating just how things should be done. I’m also open to new experiences.That part of my personality alone has helped make me a good leader.”

To acquire the training she would need to become an executive physician, after completing her residency, she earned a master’s in science management at New York University’s Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. Administrative roles soon followed: vice-chair of the emergency department and medical director at St. Luke’s Cornwall in upstate New York, attending physician at Mount Sinai in New York, and, for eight years, director of urgent care at Mount Sinai in Queens, New York.

Eight years ago, she was appointed chief medical officer at Hoboken University Medical Center, in Hoboken, New Jersey, where she served until last year when she moved to Community Medical Center, a large, acute-care hospital, about an hour’s drive south of New York City, along the New Jersey coast.

Eight years ago, she was appointed chief medical officer at Hoboken University Medical Center, in Hoboken, New Jersey, where she served until last year when she moved to Community Medical Center, a large, acute-care hospital, about an hour’s drive south of New York City, along the New Jersey coast.

Neblett’s arrival at Community Medical Center coincided with one of the worst global health crises in a century. She had barely settled in when, in early March, the hospital began seeing its first wave of Covid-19 patients. Since then, she has spent six days a week, 12 hours a day at the hospital.

“Every day we come in and look at what’s going on,” she says. “We have a whole entire command center with a board that has exactly how many patients are here, how many are sick, how many are not sick, how many are on vents, if there are any new deaths. We’re looking at every single thing in the hospital, where everybody is, monitoring the changes from yesterday to today to see who and what needs our focus, what went well, what didn’t go well.

“I’m seeing the big picture of where things should go and how things should happen. There’s a lot of input coming from the way the er doctors want to do things and the way the icu doctors want to do things. We’re a part of a very large system, and I make sure that all the protocols and policies fit together with what we are currently doing and what’s supposed to happen.”

Important to Neblett is that the health professionals she oversees feel supported. “Since the executives are not face-to-face with the patients and the danger of infection, it’s important to show those on the front lines that we’re here for them, up close, not just from afar with our feet up and texting on our phones,” she says. “So we actively make rounds on the floors to see what we can do for them. It’s important for us to be here on the weekends; we walk around all over the hospital just to let them know that we’re in this fight together.”

Neblett’s schedule leaves little time at home with her husband, Rich Cronin, and for running or playing tennis. For now, she runs only once a week on her day off.

In the midst of all this, she says, she has learned an important lesson. “One of the things that I’m not very good at, and which I’ve learned to get better at, is outwardly communicating everything that I’m thinking and doing. In the first week of the pandemic crisis, a lot of my doctors and colleagues were asking, ‘What’s going on?’ So over those first several weeks, I learned how to better communicate and that has been helping everyone.”

“In fact,” she said laughing, “someone the other day actually said, ‘Stop communicating so much,’ so all my doctors now know exactly what’s going on, good or bad, and the truth to all of it. Without getting political, what’s going on right now with the government is ‘Give us true information and we will be fine. Don’t lie to us, just really be open and honest. No matter what it is, we can deal with it.’ All people want is true information.”

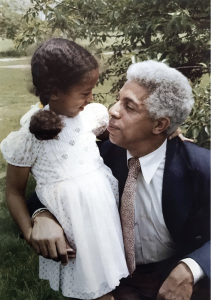

Neblett at four with her father, Roy.

Neblett credits her father for giving her confidence that she could do whatever she set her mind to. Roy Neblett, who early in his career served on Boston Mayor Kevin White’s staff, in later years operated his own accounting firm in Mattapan Square, where Neblett’s mother, Patricia, also worked.

“The most influential person in my life was my dad,” she says. “He was a wonderful, strong figure, and he had a very specific image of who he wanted his daughter to be. He taught me to be very independent. I knew how to change my own oil, how to change a tire. I knew what everything in a toolbox was. That was all very important to him. It was important to him that I not throw a football ‘like a girl,’ so to speak, that I know how to hold it on the laces and spiral. He didn’t want it to ever be said that ‘she does something like a girl,’ which, as you know, is not always a positive thing when said in that manner.”

Their family was close knit. Neblett and her brother, Touré ’89, a music journalist and culture critic now living in Brooklyn, grew up in Randolph, Massachusetts, not far from the Milton campus. A lifelong tennis player, their father instilled a love of the game in both his children. When Neblett competed in the nationals at Emory, her parents flew to Atlanta to watch.

“It was so exciting to see him watch his daughter play tennis at that level,” she recalls. “There were the umpires sitting on the seats and ball boys and girls running around. It was all the pomp and circumstance and glitz and glamor.” After his death, in 2018, Neblett paid tribute to her father by organizing a tennis tournament in his memory.

“Tennis was his sport,” she says.

Neblett with Kerin McGlame Adams ’91, her doubles partner at both Milton and Emory

Neblett also credits Milton for what she has accomplished. “I truly believe I wouldn’t be where I am today were it not for my dad and Milton Academy—the two most influential forces in my life,” she says. She remains close with many of her Milton classmates. “Milton helped to formulate who we are,” she says. “Who we were and what we did back then is really reflective of the people we became.”

Neblett wants her story to serve as more than a tale of personal achievement—as an example of what’s possible for young Black girls. Today, according to the Journal of the National Medical Association, Black females represent only 2 percent of physicians in the United States. Fewer still become chief medical officers.

“I was raised to believe that I can do anything,” she says. “I have tried to be a role model to my community so that other Black girls think the same thing, regardless of where they’re from. I volunteer my time and give back both in this country and abroad.” She recently traveled on a medical mission to Ghana where she helped organize almost 500 volunteers.

As the first wave of the pandemic began to subside in the New York/ New Jersey area last spring, Neblett and her team began planning for what lay ahead. “What we’re looking at and preparing for now is based on what we know and how we should do things differently in the future. How should our hospital be arranged? Should we have different entrances? Should we have different things slightly off campus or outside? How do we reassure the public that it’s safe to come in? Those are the types of things we have to think about, because there will be another wave, but we don’t know what it’s going to look like just yet.”

For now, Neblett continues to work long hours—managing a health crisis at her new post that is likely to reverberate for years to come. This experience, she says, has only helped reaffirm the choice she made as a young girl eager to learn more about a disease that had befallen her Milton classmate.

By Sarah Abrams

Photographs by Brad Trent