The Joys (and Tribulations) of Writing for TV

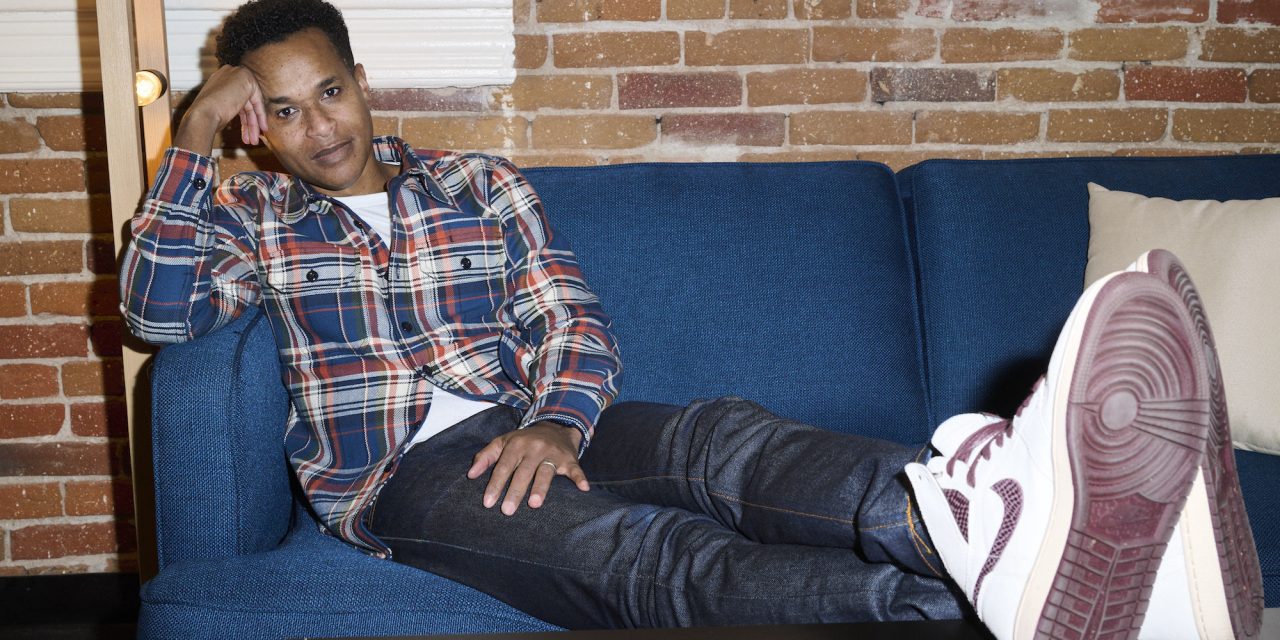

Robb Chavis ’94 helped negotiate the deal that will benefit more than 11,000 screenwriters—and he’s one of them.

Story by Steve Nadis

Photography by Peter Yang

When you hear Robb Chavis ’94 talk about writing for television, you can tell straight off that this is a guy who loves his job. Like most people, he’d like to advance in his career. But he’s also intent on preserving the profession as a whole. And that is pretty much what he has fought for as a member of the Writers Guild of America West board of directors, as well as a member of the negotiating committee that prevailed over studio heads during the 2023 writers’ strike. Serving in that capacity, Chavis fought to establish conditions that will enable people like him to make a decent living in their business, while creating quality programs that people might actually want to watch.

With an extensive background in both law and entertainment, he brought the right set of skills and lived experience to the negotiating table. Fortunately, Chavis’s side achieved a favorable settlement of the 148-day strike, which means he’s now back at the day job that also happens to be his dream job. Although there’s nothing he’d rather be doing than writing for television, Chavis took a rather circuitous route in getting there. And when he was younger, he never regarded his present occupation as a possible career choice.

When Chavis entered Milton Academy as a 10th grader in 1991, he was—by his own admission—an uninspiring writer. He’d come to Massachusetts from Atlanta public schools that were not of the highest caliber. When the first paper he wrote for English class was returned to him, the teacher, Walter McCloskey, said, “Please come see me after class”—six words that no student wants to hear.

Chavis with classmate Rahsaan McGlashan-Powell ’94 at Graduation

“My book reports had been written in a dull and very simplistic style,” Chavis notes. His compositions, in fact, could accurately have been called prosaic. “McCloskey taught me to write critically and creatively,” Chavis says. And for the first time, he came to enjoy writing. But the plan he’d formulated early on was to go into politics or something policy-related. Chavis majored in public policy as an undergraduate at Duke University and followed up on that by going to Harvard Law School, “still intrigued by law, politics, and policy,” as he puts it. After graduating from Harvard Law in 2001, he took a job at an Atlanta law firm, where he worked in the area of intellectual property, engaged in trademark and copyright litigation. He soon switched jobs, becoming in-house counsel at a multicultural ad agency near Detroit. At the agency, Chavis was surrounded by people who were doing creative things—telling stories, composing visual imagery, and finding music that would establish just the right mood. “That milieu started an itch I couldn’t ignore,” he says. “I always liked creative writing, but I never considered the arts a real option. With all my education, I thought I had to do something more serious, like business or law.”

Nevertheless, he began to do some writing on the side—mainly short stories and blog posts. Some- how, in the midst of that, he “discovered the world of TV, recognizing that you could create great characters whose stories might mean something to people. Moreover, I thought I might actually be good at this.” Chavis decided to go all in. In 2011, he quit his job and moved to Los Angeles. So did his wife, who had been working as an attorney at the same ad agency.

“It felt kind of crazy,” Chavis admits, “but we still made that leap.” Once in LA, he read books on screenwriting while publishing some stories on the internet. Reginald Hudlin—a well-known screenwriter, director, and producer—came across some of Chavis’s online material and told him it was interesting. Hudlin let Chavis know that he was funny and capable of writing for TV, which provided a great confidence boost.

During his first year in California, Chavis wrote an unsolicited, so-called “spec” script for 30 Rock, a sitcom he really liked. He submitted the script as a writing sample to NBC, the network that produces the show, and it was good enough to get him admitted to a highly competitive NBC program called “Writers on the Verge,” to which just eight people are selected from among roughly 1,600 applicants. The Verge program ran for six months, from the fall of 2012 to the spring of 2013, during which time Chavis gained a lot of practice in writing and revising scripts, getting tons of helpful feedback along the way. He also had a chance to talk with network executives. When the program ended, he assumed he would be “fast-tracked into a job,” but he had to wait a year before being hired by NBC in 2014 as a screenwriter for Bad Judge—a show about a judge whose personal life was a mess.

During his first year in California, Chavis wrote an unsolicited, so-called “spec” script for 30 Rock, a sitcom he really liked. He submitted the script as a writing sample to NBC, the network that produces the show, and it was good enough to get him admitted to a highly competitive NBC program called “Writers on the Verge,” to which just eight people are selected from among roughly 1,600 applicants. The Verge program ran for six months, from the fall of 2012 to the spring of 2013, during which time Chavis gained a lot of practice in writing and revising scripts, getting tons of helpful feedback along the way. He also had a chance to talk with network executives. When the program ended, he assumed he would be “fast-tracked into a job,” but he had to wait a year before being hired by NBC in 2014 as a screenwriter for Bad Judge—a show about a judge whose personal life was a mess.

“I got to use some of my legal background and turn it into comedy,” Chavis says. He really enjoyed the collaborative aspect of the process, meeting with his peers in the writers’ room to work out overall story lines and then breaking that down into individual scenes and beats. “It was a great experience,” he says, “but like many shows, it only lasted one season—13 episodes—and the second it was done, you’re out of work, looking for the next thing.”

The next thing turned out to be the NBC sitcom Truth Be Told, which lasted just 10 episodes in 2015 before the plug was pulled. A year later, Chavis was hired to work on Superior Donuts—a CBS comedy, set largely in a donut shop, that starred Jermaine Fowler and Judd Hirsch. “That was the show that gave my career some traction,” Chavis says. “I started moving up the ladder, eventually becoming an executive story writer, where I learned some of the ins and outs of producing a TV show.”

That paved the way for what Chavis calls “the best job I’ve ever had in tv”—a four-year stint with Blackish, which he joined in 2018 for season five. He started as a co-producer and stayed on through season eight, the show’s final season, which wrapped up in April 2022. He and others were nominated for an Emmy in 2021 for Outstanding Comedy Series.

In 2022, Chavis won the Humanitas Prize for his script “If a Black Man Cries in the Woods,” which aired one week before the series finale. That episode explored the issue of Black male vulnerability, Chavis says. “It was about the his- tory of Black men suppressing their emotions and feelings because they thought they had to be tough.” The show’s three main male characters— father, son, and grandfather—go to a cabin in the woods, forging a new kind of bond after finding ways to express themselves honestly.

“Comedy is not just for laughs,” Chavis explains. “It can be a great way to provoke serious conversations. You can present ideas in nonconfrontational ways that disarm people while still entertaining them.”

He was sorry the show had to end, but he was glad that the writers knew in advance and thus had the opportunity “to leave our [fictional] family, the Johnsons, in a place that seemed hopeful.”

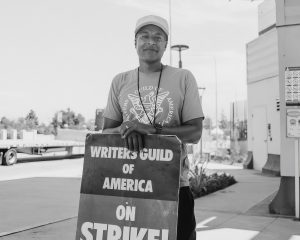

About a year later, in March 2023, Chavis and other Writers Guild representatives began to talk with the studios about the general contracts for writers that were set to expire on May 1 of that year. Chavis was selected for this team because of his background in law—and intellectual property in particular—along with his work in business and television. A major grievance concerned “residuals”—payments related to the reuse of a writer’s work—which were not as generous in streaming models as they were in broadcast television and syndication. At the time, 50 percent of Guild writers were working at the minimum wages established in the previous contract, which was clearly an untenable situation. When it became apparent on May 1 that a deal could not be made, the Guild negotiators voted to initiate a strike. “We were out on the picket lines the next day,” Chavis says.

Chavis on the WGA picket line.

“One of the things that made us successful was that almost the entire town, and ultimately most of the nation, was behind us,” he adds. “We felt a lot of public support, and that made us stronger.”

Negotiations resumed in mid-August, and the strike ended on September 27. “The thing that makes me happiest about what we accomplished is that, for the first time ever, we got something for everyone—things that made every member’s life better,” Chavis says. There were provisions, for example, that guaranteed feature film writers the chance to write a second draft after getting feedback. Rules were imposed to keep people in both TV and film from being forced to rely on artificial intelligence (AI) tools.

Chavis is thrilled that he and other writers are working again—this time under much fairer terms. The Frasier reboot that Chavis worked on before the strike began airing on October 12, 2023, two weeks after the strike was resolved. A second season may be in the offing. Meanwhile, Chavis also has a deal to develop a new half-hour series for CBS—a project he is eagerly pursuing.

“I am happy to have been part of a good fight, but also happy to be part of a network that is moving forward with new projects,” Chavis says. He’s glad to see writers and studios working together again. “Hopefully, everyone now understands the value of writers and the value of making the things that make these companies successful.”

“We are in this together,” he adds. Chavis had uttered those same words about the writers’ strike. The only thing that has changed is the “we.” But the sentiment behind it is the same. And it’s genuine.

Steve Nadis is a freelance science writer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He’s a contributing editor for Discover and a contributing writer for Quanta have appeared in dozens of other magazines.