A Change of Heart

A trip that Tony Dior Gaenslen ’59 took during spring break of his senior year changed the course of his life.

Story by Elaine McArdle

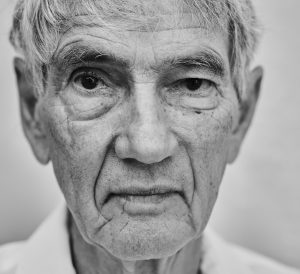

Photographs by Walter Smith

Tony Dior Gaenslen ’59 entered Milton Academy as a self-described “shy” and “nerdy” kid, the Texas-born son of a politically conservative family. He was so enamored of Robert E. Lee that he wrote his senior history paper describing him as the greatest general of the Civil War and a man of unimpeachable character.

His father was an oilman, his mother a devout Catholic from Normandy, France, whose first cousin was the iconic fashion designer Christian Dior, and as a teen Gaenslen abhorred labor unions and the Democratic Party. When Arkansas Governor Orval E. Faubus refused to allow Black students to enter Little Rock’s Central High School, in 1957, “I thought it was a mistake on Eisenhower’s part to send federal troops to the South,” says Gaenslen.

But after a profound transformation during his senior year at Milton, Gaenslen has spent his life as a passionate advocate for civil rights. He endured 11 days in a Mississippi jail during the Freedom Summer of 1964 and was part of the March on Washington in 1963 when Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. As a civil rights lawyer, Gaenslen was a close advisor to the labor leader Cesar Chavez, who co-founded the National Farm Workers Association.

But after a profound transformation during his senior year at Milton, Gaenslen has spent his life as a passionate advocate for civil rights. He endured 11 days in a Mississippi jail during the Freedom Summer of 1964 and was part of the March on Washington in 1963 when Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. As a civil rights lawyer, Gaenslen was a close advisor to the labor leader Cesar Chavez, who co-founded the National Farm Workers Association.

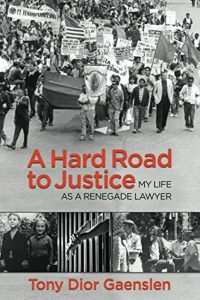

Gaenslen and his family held “all sorts of beliefs that I absolutely do not believe now,” he says. “So you can see what I’ve come from.” Or, as he writes in his memoir, A Hard Road to Justice: My Life as a Renegade Lawyer, published in 2020 by Pearl Street Press, “I may not have been the least likely member of Yale’s class of 1963 to plunge into a life of activism, but I was certainly a strong contender.”

He can pinpoint the precise moment of his personal metamorphosis. During spring break of his senior year at Milton, he and his friend Joe Bradley ’59 set off on a bicycle tour of Civil War battlefields in Virginia—a “pilgrimage,” as he puts it—so that Gaenslen could visit the sites of his hero’s greatest victories, including the Battle of Cold Harbor, outside Richmond.

“I had a life-changing experience at Cold Harbor,” Gaenslen recalls. The two teens stopped for lunch at a roadside shack, which had separate service windows for white and Black customers, and the white owner was very friendly to them. But a few minutes later, Gaenslen witnessed her shouting at two Black customers. “She was handing out generous measures of abuse and contempt,” he says. “The image I have is them hanging on to their dignity like they were clinging to a rock during a hurricane. I realized at that moment I was a co-conspirator in a conspiracy to deprive them of their dignity.”

As he writes in his memoir, “The battle of Cold Harbor had just claimed another casualty. Me. It killed off my identification with Lee and the Old South. When the Greensboro, North Carolina, sit-in movement leaped into national prominence some 10 months later, I knew which side I was on.”

His transformation was rapid and permanent. He was inspired to become a lawyer by his beloved French grandfather, Henri Dior. During the infamous Dreyfus affair of the 1890s, when the Jewish French army officer Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of treason, his grandfather “stood up for Dreyfus and he wanted me to know that when I was about 13 or 14,” Gaenslen says. “He was one of only two people in his bourgeois Catholic family who did.” But the civil rights movement was heating up, and to his parents’ dismay, Gaenslen put his law school plans on hold. “I thought I would plunge into the civil rights movement and spend a year,” he says. Instead, he notes, with a laugh, “I’ve spent my whole life.”

—

After Yale, Gaenslen led a program in Philadelphia that tutored inner-city children, participated in the March on Washington, and became a committed pacifist and ultimately a Quaker. In the summer of 1964, he headed with hundreds of other activists to Mississippi to register voters. Working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he found himself in Greenwood, Mississippi—notorious as the town near where Emmett Till was murdered in 1954—where he lived in a Black neighborhood in a heavily guarded SNCC “safe house.” He writes, “The hours I slept behind its locked doors were the few each day that I was not intensely afraid.”

As they registered voters, he and 13 others were arrested on bogus charges and thrown in jail. Gaenslen’s description of the next 11 days is harrowing. The sadistic warden delighted in threatening him and another white activist, and Gaenslen overheard a group of white prisoners plotting to kill them. They were finally rescued with the help of a lawyer from what was then the only racially integrated law firm in the South. Two months later, three young civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Mickey Schwerner, were murdered in Mississippi. “I had escaped their fate by the narrowest of margins,” Gaenslen writes.

He is proud of his work there, but after he graduated from Cornell University Law School, his arrest in Mississippi, which he included on his résumé, “was a kiss of death,” he says. With help from a Cornell professor, he landed an interview with Arthur Leff, chief counsel to the chairman of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), in Washington, D.C., who was interested in only two things on Gaenslen’s résumé: his arrest in Mississippi and the fact that he’d played on the second tennis team at Milton, where he was a “decent, but by no means great, tennis player,” he explains. Leff offered Gaenslen a position as an attorney-advisor to the NLRB chairman. “In my wildest dreams I had never dared to hope for such an outcome,” he writes.

Gaenslen—who as a teen had scorned labor unions—enjoyed his tenure as a lawyer for the NLRB and, later, for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. But it was his next role, working with Chavez and the United Farm Workers Union, that marked a high point in his career. Chavez gave him “the opportunity to work on the cutting edge of a labor movement dedicated to bettering conditions for migrant workers, the most exploited and vulnerable labor force in America,” writes Gaenslen. He successfully defended a number of cases in rural California in behalf of migrant workers who were penalized for trying to organize, but the work took him away from his young family, so he moved to Ithaca, New York, where he still lives with his second wife, Annie. There, he quickly found himself representing the Cornell Eleven, a group of women faculty who’d been denied tenure. “Nobody would take the case,” he says. “I thought, what kinds of problems could white, middle-class women have?” With a laugh, he adds, “I soon found out.”

For five years Gaenslen fought his alma mater and its coterie of high-priced defense lawyers before negotiating a settlement. “It was an incredibly wonderful experience,” he says, but he didn’t have the stamina to continue with that level of major litigation, so he transitioned to representing plaintiffs in Social Security disability and workers’ compensation cases. “I loved the workers and representing them and telling them how to tell their stories on the stand and bring out who they were as human beings,” he recalls. He retired from law practice in 2008.

His lifelong dedication to civil rights was not without personal cost. After Gaenslen postponed law school to work with inner-city children, his outraged parents refused to attend his Yale graduation or his wedding. “My idea of what I wanted to do with my life was totally incompatible to the way they were pushing me,” he says. And his long hours working with Chavez led to one of the most wrenching moments of his life, described in his memoir, when his little boy begged him not to leave for a speaking event.

“I lament the fact that when I was ‘saving the world,’ I was not spending time with my kids,” he says. “If I had it to do again, I’d say to hell with the people supposed to be listening to me—they’ll find someone else to talk.” Today Gaenslen enjoys a loving relationship with his two children, and he says, “I am incredibly lucky.”

In his memoir, Gaenslen calls Milton “The Academy.” He arrived as an eighth-grader from Venezuela, where his father was working for a major oil company. “I got a really good education at Milton,” he says. He was particularly inspired by faculty member A.O. Smith, who taught honors English. “A.O. realized I wanted to write, which my parents strenuously objected to,” says Gaenslen, who is proud of applying his writing talent to crafting legal briefs for his underdog clients.

How does he compare today’s turbulent times with the 1960s? “We made a huge difference in many, many ways,” he says, “but we’ve regressed a lot, and we have problems like climate change and Black people being gunned down in the streets in record numbers and white male Christian supremacy being waved around as a virtue. So what do I do with that? Well, I do not know how to give up.

“My whole thing is about being courageous,” he adds. He finds hope in the many young people, including Greta Thunberg, “who have guts. I’m just enormously encouraged by that.”

Elaine McArdle, based in Saratoga Springs, NY, is an award-winning journalist and book author.

A graduate of Vanderbilt University Law School, she writes for the Harvard Law Bulletin, Northeastern Law Magazine, Harvard Ed. magazine, and many other publications.