Comics and More

by Amy Kurzweil ’05

My mother likes to tell this story: It was Parents Day at Milton, honors math class, and there I was, for the whole class, gaze fixed on the margins of my notebook, doodling. This was the latest in a subtle but long-suffering rebellion. I quit Math Club after sixth grade. At Milton, I’d forgone chemistry to fit two studio art and two creative writing classes into my schedule, plus dance. I was not going to be an engineer, an astrophysicist, or a doctor.

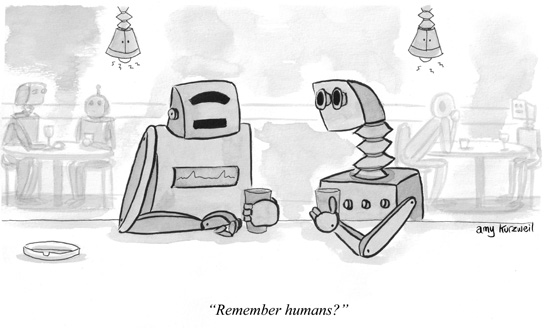

Now I doodle for a living. I also teach, and I let my students draw in class (often I force them to draw in class). I know that when you’re drawing, you’re still listening, that drawing can often facilitate remembering. Cartooning is a specific way of drawing, and it’s a specific way of seeing. A cartoon flattens and simplifies some dynamic of human life, and humor adds force to the observation. The reader says “A-ha!” recognizing a broad message, while also experiencing the unique style of the messenger, the human touch of one individual’s pen mark on paper.

I began submitting cartoons to The New Yorker in 2015. I’d just finished and sold a 300-page graphic memoir (Flying Couch — check it out!). It took eight years. I thought it seemed fun to finish a project in less than eight years. (One cartoon takes a few hours.) The first cartoon I sold was about self-driving cars. Technology has been making our lives better and worse since fire. How we respond to its miracles and damages reveals more about the nature of the human than of the machine.

I began submitting cartoons to The New Yorker in 2015. I’d just finished and sold a 300-page graphic memoir (Flying Couch — check it out!). It took eight years. I thought it seemed fun to finish a project in less than eight years. (One cartoon takes a few hours.) The first cartoon I sold was about self-driving cars. Technology has been making our lives better and worse since fire. How we respond to its miracles and damages reveals more about the nature of the human than of the machine.

I believe a well-done cartoon reminds people with authority that the rest of us are paying attention. I was listening in math class, but I was listening the way an artist listens, attuned to the way numbers make us feel.