Food Makes Learning Fun

TEACHING LANGUAGE THROUGH FOOD

In the 20-minute video, GIANNA GALLAGHER ‘21 stands in her home kitchen, naming the measured ingredients laid out before her in fluent French. She then begins to make the batter for madeleines, the classic French tea cakes famously referred to in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. It’s a project for French 6, the highest level of French class at Milton, and just one of the many moments when food is used as a tool to learn a language in the classroom.

In the 20-minute video, GIANNA GALLAGHER ‘21 stands in her home kitchen, naming the measured ingredients laid out before her in fluent French. She then begins to make the batter for madeleines, the classic French tea cakes famously referred to in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. It’s a project for French 6, the highest level of French class at Milton, and just one of the many moments when food is used as a tool to learn a language in the classroom.

“The basic component of learn- ing a language is to learn the culture—they go together,”says Severine Carpenter, an Upper School French teacher. “Food is a natural component of this and it is fun to use in class, because everyone loves food!”

French teacher Cédric Morlot says the beginner textbooks for the French and Spanish classes always have chapters focused on vocabulary for food and eating. Food top- ics, he says, are good icebreakers and get the students talking.

“They want to speak about food, such as their favorite snack,” he says. “It’s a subject that is passionate to them, so in beginner classes we can have a conversation about pizza that turns into a debate about whether you should put pineapple on pizza.”

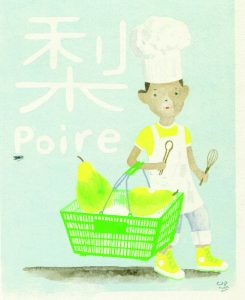

Food topics also work well when students perform skits in class, such as pretending to be at a restaurant or shopping at a market. As the students advance in the language and order food in an actual restaurant, Morlot says, whether locally or on an exchange program, “they are very proud of that moment, which is the goal for us language teachers beyond grades.”

However, introducing words for specific foods or discussing food is “trickier” in Milton’s beginner Chinese classes, according to recent- ly retired Chinese teacher Shimin Zhou. The U.S. State Department’s Foreign Service Institute classifies Chinese as one of five “super-hard languages”—those that are exceptionally difficult for native English-speakers.

The English language is Germanic with some words also de- rived from Latin roots. French and Spanish are Romance languages, which evolved from Latin. The word “pastry” in English is “pâtiserie” in French, with both originating in the Medieval Latin pasteria from the Latin pasta. No such re- lated derivations exist between English and Chinese words. And beginner Chinese-language learners are also learning tones and the characters for writing.

In Chinese classes, Zhou says, students may discuss food in “com- pare and contrast” formats, such as an American breakfast versus a Chinese breakfast, because food choices and ingredients can be quite different.

“In the higher levels of Chinese, we talk about how the names of certain dishes come from a famous dynasty or poet,” says Zhou. “So it brings in the cultural and historical roots of Chinese food. Just like the language, Chinese food can be very complicated and not so easy to trans- late to English equivalents.”

Carpenter says she has taught recipes—such as crepes and galettes—that reflect her background in the Brittany region of France. In the higher-level classes, food topics lead to lessons on the economy and the natural resources of a Francophone country. Lessons on cultural norms and food habits, such as why people in France eat something sweet late in the afternoon, are also taught.

Outside the classroom, student culture clubs often share food special to them during certain events and holidays, such as Zhou’s dumplings on Lunar New Year or latkes at the Jewish Student Union’s Hanukkah celebration.

By Liz Matson

Illustration by Brian Cronin