Exposure to the Arts Teaches Important Life Skills

CLASSES IN THE ARTS OFFER STUDENTS THE TOOLS THAT HELP THEM TO THINK CRITICALLY AND SOLVE PROBLEMS

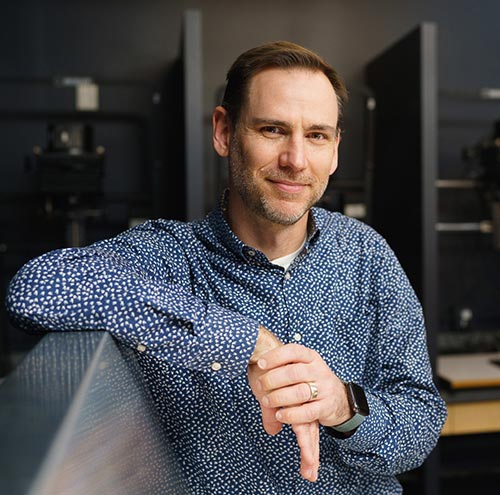

Before arriving at Milton five years ago, photography teacher Scott Nobles worked for many years in New York City as a commercial photographer, with clients that included Canon, GE, Boston University, Simon & Schuster, Penguin Books, and various magazines, among others. He also taught photography at colleges in the New York area, including New York University and the Fashion Institute of Technology. He continues to maintain a commercial photography business. Shortly before the end of the fall semester, Nobles sat down with Milton Magazine to talk about teaching and helping Milton students connect to their inborn creativity.

WHO TAKES ART AT MILTON?

WHO TAKES ART AT MILTON?

Every student in their freshman year is exposed to the full spectrum of what Milton has to offer in the arts—from the visual to the performing arts. The freshman visual arts requirement is a semester long, and during that time we offer a multitude of units that touch upon each genre of art—photography, drawing and painting, sculpture and ceramics, film and video, and technology and design. They dabble; they get one assignment from each of the genres that we offer. Then, later, sometime before they graduate, they choose one course in the arts to fulfill their graduation requirement.

CAN YOU DESCRIBE YOUR PHOTOGRAPHY STUDENTS?

Every student in my photo program after freshman year has elected to take my class. They may be taking it because they’re really excited about photography, or they may be just throwing a dart at the board to see what happens. But almost 100 percent of the time, once they’re in the class, they realize they can be creative, even if they didn’t think they were or even if they don’t have an arts background. That’s really what we’re striving to teach in the visual arts program—that everyone has creativity in them. And I think we reach most students. They get it. They are extremely talented and can apply their creativity to other areas of their lives.

WHAT’S IT LIKE TO SEE THAT LIGHT GO OFF WHEN THEY GET IT?

Oh, it’s wonderful. That’s why I keep coming back to teaching. I love it. To see that spark, to see that “aha” moment, is lovely. It happens with most students; it’s just that they may be on a different trajectory in terms of when.

WHAT’S THE PROCESS FOR GETTING STUDENTS TO THAT “AHA” MOMENT?

It’s tricky in photography because, as I explain to my beginning students, photography is both science and art. It’s technology plus creativity. I start from the ground and slowly elevate their skill level in both technique and aesthetics. Many of them find it daunting to pick up a camera for the very first time. It’s got so many buttons, and it’s very different from the smartphone camera that they’re so used to.

The first couple of assignments are really just about exploring— looking up, looking down, getting low, getting high with their cameras. Then it slowly builds. The second assignment, we start playing around with a few additional buttons on their cameras and, at the same time, train their eyes a little bit more to look for specific elements in a composition. It could be lines or shapes or colors. As you build from one unit to the next, you’re taking the knowledge that you’ve acquired and adding to it.

I’m at a point in the semester right now where the students know the camera inside and out. They have a good understanding of how to build a strong composition. Now we’re starting to have a bit more fun. We start to dabble with the back side of tweaking an image in Photoshop, or diving into the lighting studio and learning how to experiment and play with controlling light. It’s not meant to be scary. It’s meant to allow them to grow, especially if they have no experience whatsoever with photography.

HOW DO YOU ENGAGE THE LESS-CONFIDENT STUDENT WHO MAY NEVER HAVE TAKEN A PHOTOGRAPHY CLASS?

I try to create a nurturing environment in my classroom. I try to teach all the students how to be respectful and how to raise everyone’s abilities— technically as well as aesthetically. One of the ways I do that is to dedicate an entire class to critiquing student work for each assignment. It’s a student-led critique with me jumping in occasionally just to offer a little bit of guidance. “What do you like about the image, and what could be improved?” Those questions can be asked of every single student no matter what level they’re at. As long as a student is open to hearing that feedback, regardless of their skill level, they will continually grow and start to realize they can improve and be more creative.

WHY IS IT SO IMPORTANT FOR STUDENTS TO KNOW THAT ABOUT THEMSELVES?

One of the key goals—for myself and for all my visual arts colleagues— is to show that the arts are for everyone and play an important role in a society. It doesn’t matter if you’re going on to college to study the arts or if you’re going to have a career in the arts. Having a foundation teaches you about being imaginative and coming up with multiple ways of tackling a problem—whether it be a visual problem or any problem whatsoever. Iteration is a big word that’s thrown around a lot, which just simply means saying to yourself, “Okay, you’ve tackled the problem this one way, have you thought about a different angle? Have you thought about a different exposure or a different lens?” The first solution is not always the best solution. Knowing that can be applied to the arts, but it can also be applied to deeper, more critical thinking in general. They can take that knowledge and apply it to being a physicist, a lawyer, or an engineer. Creativity is vital to any career you go into.

Illustration by Karolin Schnoor