Hard Truths

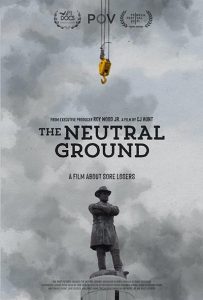

COMEDIAN AND FILMMAKER CJ HUNT ’03 CONFRONTS AMERICA’S DISTORTED HISTORY AROUND RACE IN HIS RECENTLY RELEASED DOCUMENTARY, THE NEUTRAL GROUND.

There’s a tense moment in the documentary The Neutral Ground when filmmaker CJ HUNT ’03 asks a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans to accompany him to the Whitney Plantation, a Louisiana museum dedicated to documenting the realistic lives of enslaved Black people in the antebellum South.

At that point, Hunt has spent significant time with the man, Thomas Taylor, and several other neo-Confederates— even attending a battle reenactment with a group who passionately insist that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights, not slavery, and that enslaved Black people were treated well by those who bought and sold them.

Taylor immediately dismisses the idea. He would “never step foot” on the Whitney Plantation, asserting that the history taught there is “bullshit.”

“An early viewer told me, ‘I was heartbroken when Taylor said he wouldn’t go to the slavery museum,’” explains Hunt, who wrote and directed the documentary. “And then that person said to me, ‘I asked myself, why did I think that’s where the film was going?’ That’s a heavy question. I also thought that that’s where the film was going.”

“I had thought, maybe this film is going to be about us converting a white supremacist and changing his mind,” continues Hunt, who is Black and Filipino. “That’s what we crave in our stories about race. We want stories of reconciliation. We want stories about racists who— after a certain number of history lessons and heartfelt moments—experience a change of heart. What people don’t hunger for are stories about the messy work of reckoning, but that’s what this film is.”

Beginning with a volatile debate over the removal of Confederate monuments in New Orleans, The Neutral Ground, which was an official selection at the June 2021 Tribeca Film Festival and premiered in July on the PBS documentary series POV to critical acclaim, explores the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, a false history that sought to justify southern secession and the Civil War. Those who insist that the monuments and the Civil War itself had nothing to do with race or slavery are well versed in the points of the ideology, Hunt says. Careful not to lend legitimacy to arguments supporting the Lost Cause, The Neutral Ground dissects the lies, highlights their absurdity, and shows how their dangerous legacy continues today.

“The lie born 150 years ago is alive in the mouths and minds and memories of people now,” Hunt says. “It is the same lie that motivates somebody to walk into a Charleston church with a gun, and it is the same lie that motivates men to defend a Robert E. Lee monument in Charlottesville, and it is the same lie that compels people to carry a Confederate flag as they storm the Capitol.”

The Lost Cause developed after the Civil War to build a sense of heritage, comfort, and justification among mourning southern white families, particularly white women who had lost fathers, sons, husbands, and brothers in the war. It claims “states’ rights” was the cause of the war. And it invokes a false memory of a peaceful, genteel South where elegant white men and women cared for everyone and everything and where enslaved people were loyal and happy, historian Christy Coleman says in the film. It ignores the brutality and violence of slavery, a system in which people were kidnapped, exploited for their labor, beaten, raped, tortured, and killed. The Lost Cause went from myth to shared memory to curriculum. At the behest of groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, public schools across the South and beyond taught its tenets as factual history until as late as the 1970s.

Monuments to Confederate leaders and slave-owners were erected not as immediate memorials in the years following the war but during later decades, as Black citizens were advancing in or fighting for civil rights. “It’s hard to argue that racism is not part of our structures in this country when you see white supremacy literally carved into a monument,” Hunt says.

Hunt had been living in New Orleans in 2015 when the city became embroiled in protests over plans to remove four Confederate monuments— statues honoring Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, P.G.T. Beauregard, and the Battle of Liberty Place—from places of prominence in a city where the majority of citizens are Black.

“At the time, I didn’t think of myself as a filmmaker,” Hunt says. “I thought of myself as a comedian aspiring to be on something like The Daily Show or Full-Frontal with Samantha Bee. My only visual language for documentary was the late-night field pieces on those shows.”

His friend and film producer Darcy McKinnon grabbed some cameras and met Hunt at a city council public hearing to film the commotion, thinking they might get footage for a satirical video. “There’s a level of vitriol from some of the white folks at that meeting, and we thought it could be funny: ‘Oh my God, look at the crazy things people are saying out loud,’” Hunt says. “But then it became clear that the city was being sued to halt the removal—a democratic decision that had already been made—and in the lawsuit it came out that contractors [hired to remove the monuments] were leaving the job due to death threats and an alleged bombing of one of their cars.”

The film follows Hunt across the South, where he speaks with historians and visits sites such as the Whitney Plantation. He travels to Charlottesville, Virginia, during the deadly 2017 “Unite the Right” demonstration protesting the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. There, he meets a white man being chased by counter-protesters. The man removes the white polo shirt that signals his affiliation with the white nationalist group Vanguard America, attempting to ward off an attack. Hunt asks him why he’s there. It’s “fun,” the man says, “just being able to say, ‘Hey man, white power. You know?’”

Hunt’s goal is to show The Neutral Ground in schools everywhere, his resolve strengthened by attempts by dozens of states to ban the teaching of critical race theory— a legal framework positing that racism is structural and embedded in American institutions—in public schools. Hunt says his next project will investigate how history and race are taught to children.

“I’m measuring my impact based on how many student screenings we do,” Hunt says. He presented The Neutral Ground to Milton students in November, when he challenged them to “Dare to be true” by confronting uncomfortable truths.

“I’m asking you to dare big,” he told students. “I’m asking you to make the motto real. Because when we dare to tell the truth, that daring is contagious, more contagious than a lie.”

Hunt spent his early childhood on Long Island before moving to Massachusetts for middle school. At Milton, he enjoyed making people laugh and being in front of an audience during speech tournaments (he competed in the humorous interpretation category) and he was head monitor his senior year.

He attended Brown University, where he performed sketch and improv comedy. He also began teaching while at Brown in a program called Summerbridge, and enrolled in Teach for America after graduating. The program took him to New Orleans, where he taught English and social studies; he also led an after- school program teaching improv, “but opening that door was like getting bitten by the comedy bug again.” He performed stand-up, improv, and sketch comedy at night while teaching, and later when he worked in the public defenders’ office.

Eventually, he landed a job at the bet show The Rundown with Robin Thede. When The Rundown was canceled, Hunt was hired at The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, where he worked as a field producer and director for three years. The whole time, he was working on The Neutral Ground, assembling a crew, traveling to shoot video, and completing the film on breaks from his day jobs. He left The Daily Show in 2021 to pursue future film projects.

Throughout The Neutral Ground, in candid talks with his father, Hunt reckons with the evolution of understanding his identity and his anger. As a young mixed-race person in predominantly white environments, “it felt like a burden to talk about race because it marked me as different,” he says.

Later in the film, Hunt participates in a second demonstration, one very different from the neo-Confederates’ battle. He joins a reenactment, organized by the visual artist Dread Scott, of the 1811 German Coast uprising—the largest revolt of enslaved people in American history. Hunt is among hundreds of participants who trace the journey of the 19th-century march on New Orleans. Scott concludes the event with a celebration honoring the heroism of the revolutionaries and their effort to fight for their own freedom and end slavery for all, decades before the Emancipation Proclamation.

Hunt, who has kept a straight face or a deadpan affect for most of the film, explains his feelings: “To me it feels like sometimes a lot of being Black is remembering pain, and wearing that pain… It is a freeing thing to be able to look at that history in a positive way, in a way that feels like we were agents of change.”

He continues, “Marching in an army of Black rebels, I realize how long I’ve been doing the opposite. I feel Blackest when I’m chasing white supremacists. Like I’m somehow earning my spot when I put myself in danger or dive back in history to dig up the evidence. But the power I feel in this moment has nothing to do with staring at whiteness. It comes from being able to see myself outside of that chase.”

The scene continues with no narration as it captures participants making music, dancing, and reveling in the recognition of an often-ignored—but very real—historical event. They wear period clothing and hold imitations of the weapons carried in the rebellion. Hunt bounces with the rhythm before realizing he’s in the shot. He turns to face the camera, and he smiles.

The Neutral Ground was awarded Best Documentary at the American Black Film Festival and Best Southern Documentary at the Hot Springs Documentary Festival. In addition to a Best Narration nod from the Critics Choice Association, the film has been nominated for Best Score by the International Documentary Association for its March 2022 awards. For information on viewing The Neutral Ground or bringing it to your classroom, visit neutralgroundfilm.com.

Story by Marisa Donelan

Photographs by Brad Trent