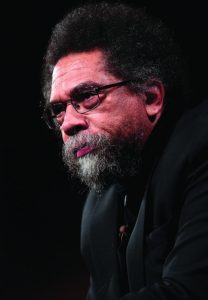

Cornel West meets with Milton English Students

“What does it mean to be human?” philosopher Cornel West asked Milton students. “How do we hold onto integrity in the face of oppression? How do we hold onto honesty in the face of deception? How do we hold onto decency in the face of insult and assault, and how do we hold on to the enabling virtue of them all—courage—in the face of catastrophic bombardment?”

“What does it mean to be human?” philosopher Cornel West asked Milton students. “How do we hold onto integrity in the face of oppression? How do we hold onto honesty in the face of deception? How do we hold onto decency in the face of insult and assault, and how do we hold on to the enabling virtue of them all—courage—in the face of catastrophic bombardment?”

West, a renowned scholar, writer, and activist, joined students taking Philosophy and Literature virtually last week. He discussed how literature can help people understand seemingly insurmountable challenges, or what Samuel Beckett called “the mess” of modern human existence.

Young people are facing catastrophic political, social, and environmental issues, West said. They may find some clarity in the work of artists and thinkers who “wrestle with catastrophe.” A self-described “Chekhovian Christian,” West said he finds healing in work that confronts disaster head-on.

“That’s James Baldwin. That’s Nina Simone. That’s Luther Vandross. That’s Raheem DeVaughn. That’s Bootsy Collins and George Clinton, the funk masters who transform their suffering into a sound that heals us, that keeps us going,” he said. “So when we talk about what it means to be human, we have to be unflinchingly honest and candid. Beethoven said he looked unflinchingly at the evil and grimness of the world and still pursued beauty. So it is with anyone with a blues sensibility: They look terror in the face and still want freedom for everybody.”

Anton Chekhov “is a bluesman with a Russian twist,” West said of his favorite writer. Chekhov’s writing is loving and compassionate, and he “never reduces the catastrophic to the problematic,” facing the challenges of life with the gravity they deserve.

People should engage with those who disagree with them in order to grapple with essential questions about humanity, said West. These questions span generations, borders, and cultures, he added.

“Faulkner lived in white supremacist Mississippi. How could we connect with him? Because he’s wrestling with the same questions,” West said. “He’s just wrong in his politics, but can be insightful in how you come to terms with loss, how you come to terms with lament. Everybody wrestles with loss.”

To practice humanity requires vulnerability, self-reflection, and bravery, and education must go deeper than formal schooling—it needs to be a lifelong commitment to investigating big questions, West told students.

“Socrates was right, the unexamined life is not worth living. But to examine life is painful and requires courage to think for yourself,” he said. “Who are you, really? You’ve got to find your own voice. Your voice is like your fingerprint. It is uniquely, singularly yours, and you’ve got to fight for it because everybody grows up being socialized into an echo—just an extension of some silo of your culture, your family, your context. You’ve got to find out who you are.”