A Focus on Reading

TAKING A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO TEACHING STUDENTS TO READ

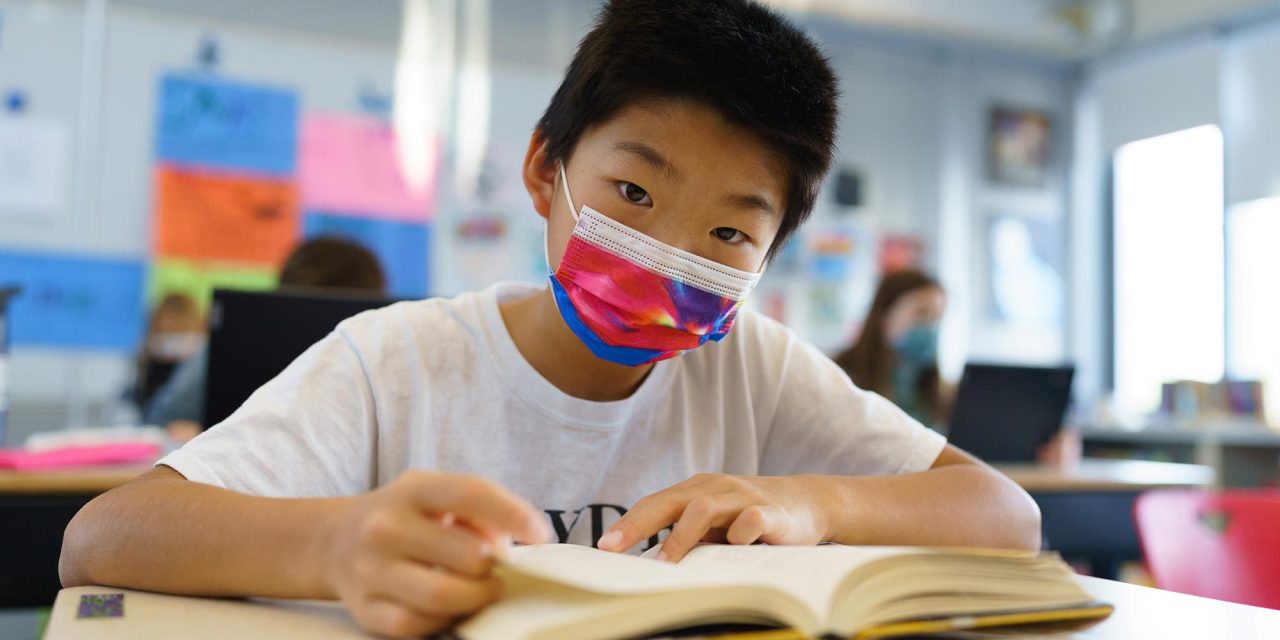

Three students sit in a crescent across from their second-grade teacher, Sue Munson, who is listening carefully as they read a storybook, each speaking just above a whisper. When Munson hears something that sticks out, she taps the table in front of a boy, prompting him to read louder.

“You’re reading very smoothly,” she tells him. “You used to put your finger on every word, but now you’re moving much faster. Great job!”

The Lower School has made reading a top priority this year, giving students one-on-one and small-group coaching as they develop, says Tyler Jennings, the Lower School dean of teaching and learning. Teachers are also focusing on phonics and the elements of language for all students, particularly the division’s youngest.

Applying methods that are strongly supported by literacy and education research, the Lower School includes explicit phonics instruction for all students, along with guided reading. Guided reading is an effective approach that involves detailed assessment of each student’s growth and areas for improvement, Jennings says. Students are then grouped with two or three others who share similar goals and are reading at similar levels of difficulty; together, and with strategic guidance from their teacher, they read through texts at a level that challenges them without discouraging them.

Applying methods that are strongly supported by literacy and education research, the Lower School includes explicit phonics instruction for all students, along with guided reading. Guided reading is an effective approach that involves detailed assessment of each student’s growth and areas for improvement, Jennings says. Students are then grouped with two or three others who share similar goals and are reading at similar levels of difficulty; together, and with strategic guidance from their teacher, they read through texts at a level that challenges them without discouraging them.

By breaking the students into groups, Munson is able to monitor their progress in real time, asking them to reread passages they struggle with and giving them positive feedback on areas where they’ve improved. She takes a holistic approach to helping the students understand each text, breaking down root words, homonyms, and letter sounds, asking them to respond to visual cues in the illustrations, and prompting them to explain how moments in the story make them feel. When they have finished their books, they’re asked to summarize the stories without retelling them and to identify the most important parts of the plot.

For some groups, Munson previews potentially tricky vocabulary words the students will encounter in their books, while other groups focus on reading with expression according to punctuation. A couple of students tap the pages with their fingers to sound out words, but are moving toward a smoother reading flow and away from more stilted speech. Others still are onto meatier chapter books. The students have their own strategies—identified by Munson—to help them improve. When certain kids are not in the groups she’s immediately addressing, she assigns some of them to partners. The peer support is an added help, she says.

“The role of the teacher is to lift them to that next level of text sophistication,” says Jennings. “What’s so important is the opportunity for the teacher to coach students in those individual goals. Instead of an abstract thing, where you take the same approach with all 12 kids in a classroom and hope that they go off and apply it, it is much more powerful to be actually teaching them during the act of reading a book.”

In addition to guided reading, Lower School teachers are following research-supported methods for teaching all students phonics, Jennings says. Educators now know that there is a false dichotomy in the choice between teaching “whole language” reading and phonics instruction. Both comprehension of texts and the foundations of words—including phonics—are critical.

A debate about the best way to teach reading has existed for centuries in the United States. Writing for the Washington Post in 2021, reporter Valerie Strauss explains that Horace Mann, the widely influential 19th-century educator, “argued against teaching the explicit sounds of each letter. He worried that students would concentrate on sounding out words rather than learning how to read for comprehension, so he argued that students should learn to read whole words instead.” A whole-language approach for reading, Mann posited, would be more engaging for new readers than studying the sounds of letters and syllables on a granular level.

An alternative to Mann’s approach to teaching reading is a heavy focus on phonics, which matches the sounds of words with individual letters and groups of letters, and phonemic awareness, which California State University- Fullerton professor and researcher Hallie Kay Yopp describes as “an understanding that speech is composed of a series of individual sounds.” Yopp explains that many kindergartners arrive at school with a “sufficient command of the phonemes that constitute their language; that is, they can pronounce most sounds clearly.” A kindergartner would understand “cat” as a “furry animal that purrs,” Yopp writes, but be unaware that the word “cat” is composed of a series of letter sounds or phonemes— the elements of a word that distinguish it from another.

This divide, which is often presented in the media and by legislators and policy makers as “the reading wars,” is significantly more nuanced—an important fact to remember when states consider new laws about how reading is taught and how students are classified as reading-disabled. “Despite a time-worn narrative, there is no sharply drawn battle line dividing experts who completely support or completely oppose phonics,” write the literacy experts and professors David Reinking, Victoria J. Risko, and George G. Hruby. Instead, reasonable differences exist along a continuum. More realistically, there are teachers who see phonics as an essential foundation for learning to read for all students, and others who see it as “only one among many dimensions of learning to read,” the experts write.

“It can be a really confusing debate to research because there are so many different camps and the pendulum has swung so wildly between different beliefs about how children learn reading best,” Jennings says, adding that the argument for teaching phonics to all young learners has gained significant ground. “Research increasingly demonstrates that explicit phonics instruction in early elementary school is essential for all children.” Some students enter school with large vocabularies and an ability to read books, but need to understand the foundations of language in the same way that less-confident readers need phonics.

“It’s really cool and impressive in its own way, but it does not necessarily mean that they understand the phonics of the words or have phonemic awareness,” Jennings says. “If we don’t give them experiences with phonics, then later on, they’re going to encounter challenges when they come up against words they’ve never seen before. They need the skills to be able to break down words and put them back together.”

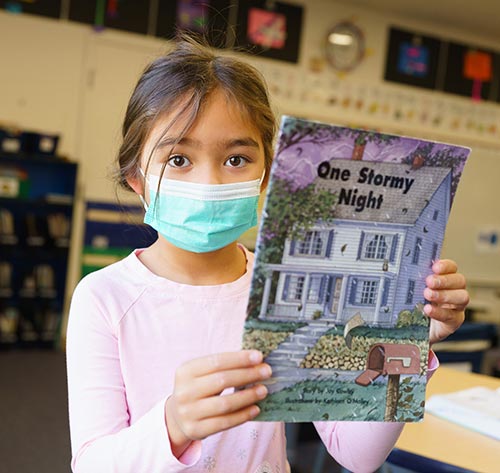

Encouraging students to read books that interest them and making reading fun are important ways to inspire students to become lifelong readers. Reading aloud is a great practice in growing students’ confidence in reading. When students are led to believe that certain books are for learning and others are for fun, it can create a separation in their minds, Jennings says.

“It’s important that we choose, at all times and in all contexts, books that are really engaging for kids,” he says. “Even though we have some serious reading goals for them during guided reading, they should still be laughing. They should be smiling and bubbling up in conversation about the book. If those things aren’t happening, then something isn’t quite right. It should be a fun, inviting activity, even though we’re engaging with the science of reading.”

By Marisa Donelan

Illustration by Adam Avery